Maharashtra—a vast state stretching from the Arabian Sea coast through the Deccan plateau to inland forests and hills—has been home to tribal communities for millennia. Long before cities rose, before kingdoms established their borders, before Sanskrit texts codified Hindu orthodoxy, tribal peoples inhabited Maharashtra’s diverse landscapes, developing distinctive cultures, languages, and artistic traditions. Their arts—painted, carved, woven, sculpted—represent some of India’s most ancient creative expressions, maintaining visual languages and symbolic systems that may stretch back to prehistoric times.

These aren’t museum relics or archaeological curiosities but living traditions, still practiced in tribal villages across Maharashtra. The Warli paint their characteristic geometric figures on mud walls. The Bhil create devotional paintings invoking their deities. The Gond fill forms with intricate patterns. The Kokna, Katkari, Mahadeo Koli, and other communities maintain their own artistic practices, each reflecting unique worldviews, environmental relationships, and cultural values.

Tribal art in Maharashtra challenges conventional art historical narratives. It doesn’t fit neatly into categories like “folk” or “fine art,” “primitive” or “sophisticated,” “religious” or “secular.” It exists on its own terms—functional yet beautiful, traditional yet evolving, simple in means yet complex in meaning, ancient in origin yet vitally contemporary.

Table of Contents

Who Are Maharashtra’s Tribal Communities?

Maharashtra contains significant tribal populations, officially termed Adivasis (original inhabitants) or Scheduled Tribes:

Major Tribal Groups

Warli: Perhaps 300,000 people living in Thane, Palghar, and Nashik districts, near the coast and hills north of Mumbai. They speak Varli, a language distinct from Marathi.

Bhil: Among India’s largest tribal groups, with Maharashtra populations in Dhule, Nandurbar, and Nashik districts. Traditionally forest dwellers and hunters.

Gond: Concentrated in eastern Maharashtra’s Chandrapur and Gadchiroli districts, part of a larger Gond population spread across central India.

Kokna: Living in Nashik, Dhule, and Nandurbar districts, traditionally practicing shifting cultivation.

Katkari: In Thane and Raigad districts, historically nomadic, now increasingly settled.

Mahadeo Koli: In western Maharashtra’s hilly regions.

Thakar: In coastal districts, particularly Thane and Raigad.

Each group maintains distinct language, customs, and artistic traditions, though some overlap and influence exists.

Traditional Lifeways

Historically, Maharashtra’s tribal communities lived through:

Forest dependence: Gathering forest products—honey, fruits, medicinal plants, fibers, timber

Shifting cultivation: Slash-and-burn agriculture on forest clearings, moving periodically

Hunting and fishing: Supplementing agricultural and gathered foods

Minimal material culture: Simple tools, weapons, utensils made from local materials

Animistic beliefs: Seeing spirit forces in nature—trees, rocks, rivers, animals

Oral traditions: Knowledge, history, mythology transmitted through storytelling, song, ritual

Communal social organization: Strong collective identity and mutual support

Relative isolation: Limited interaction with mainstream Hindu society and its hierarchies

These lifeways shaped artistic traditions—art serving ritual needs, using available materials, expressing animistic worldviews, transmitted orally and experientially.

Contemporary Situation

Today, tribal communities face profound challenges:

Land alienation: Forest laws, development projects, and population pressure reducing traditional territories

Cultural pressure: Education, media, migration pushing assimilation into mainstream culture

Economic marginalization: Poverty, limited opportunities, exploitation

Identity negotiation: Balancing tribal heritage with participation in broader Indian society

Yet tribal identity persists, and artistic traditions remain vital cultural expressions—sometimes sustained through sheer determination, sometimes supported by external interest and markets, always rooted in communities’ sense of who they are.

Warli Art: Geometry of Daily Life

Origins and Antiquity

Warli painting may be Maharashtra’s most internationally recognized tribal art. Its extreme geometric simplification and ritualistic character suggest ancient origins.

The style’s resemblance to prehistoric rock art—stick figures, animals reduced to essential forms, geometric patterns—has led scholars to speculate about continuity with Neolithic traditions dating back 10,000 years or more. While impossible to prove definitively, the visual similarity and the Warli’s own claims of ancient practice suggest this art form carries forward extremely old visual conventions.

Warli oral tradition doesn’t date the practice—it simply “always was,” passed from ancestors time beyond memory, as fundamental to Warli identity as their language or agricultural practices.

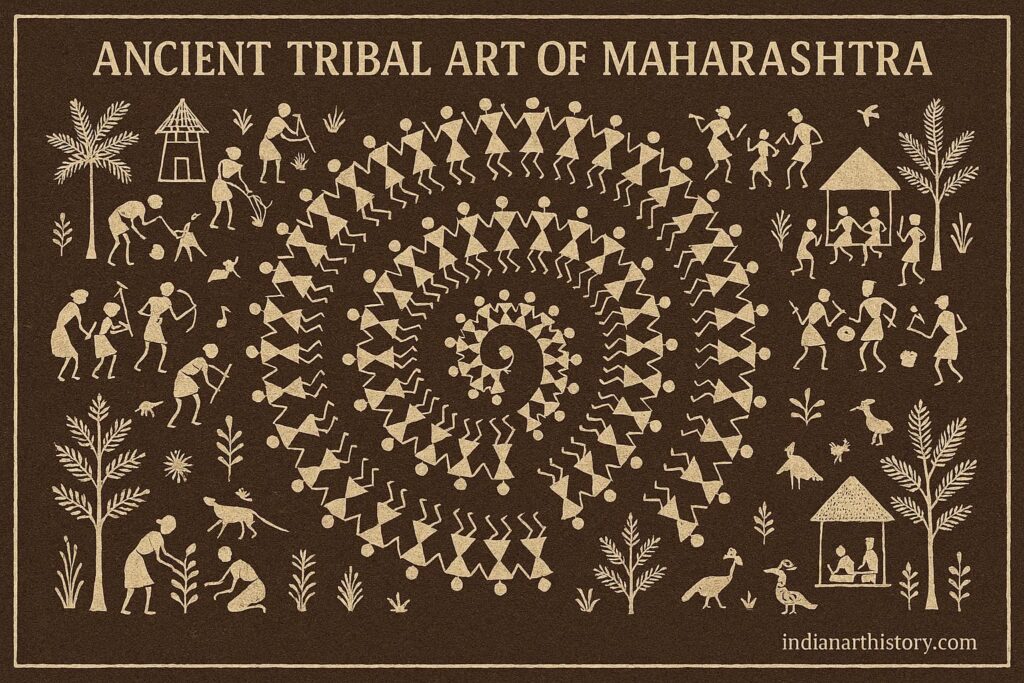

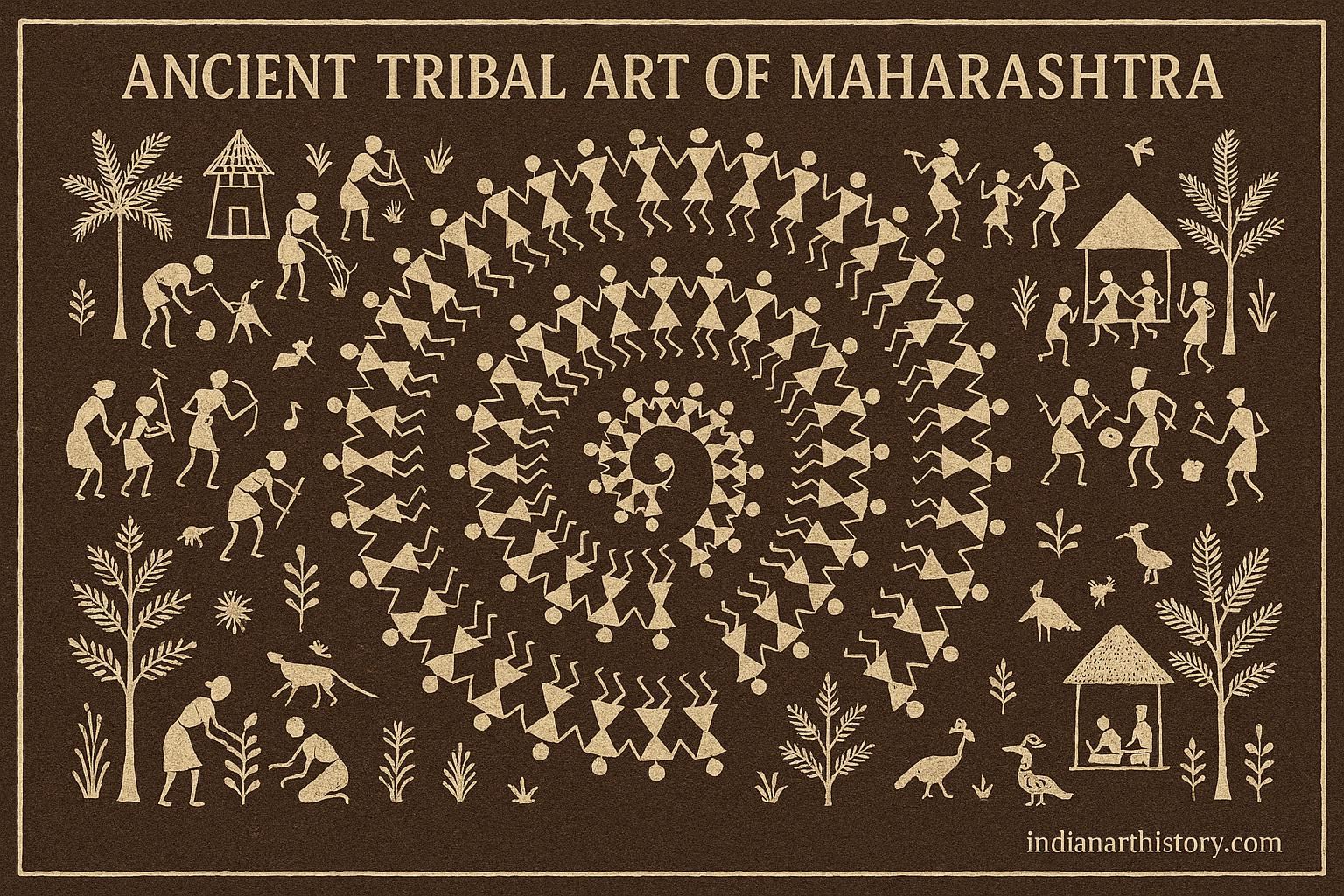

Visual Language

Warli painting employs a radically simplified visual vocabulary:

Basic shapes:

- Triangle: Represents human torso

- Circle: Represents head

- Line: Represents limbs

Human figures: Constructed by combining two triangles (one pointing up for hips/legs, one pointing down for torso), a circle for head, lines for arms

Animals: Simplified to essential geometric shapes—triangular bodies, circular heads, stick legs

Trees: Triangular or linear forms, sometimes with circular fruits or flowers

Houses: Square or rectangular forms, sometimes with peaked roofs

Agricultural implements: Simplified linear representations

This geometric reductionism creates instantly recognizable aesthetic—figures abstracted to near-symbols, readable yet clearly not attempting naturalistic representation.

White on Red-Brown

Traditional color scheme is starkly limited:

Background: Red-brown mud walls, the natural color of earth and cow dung plaster

Paint: Pure white made from ground rice mixed with water and gum

Contrast: The white figures stand out dramatically against dark background

Symbolic dimension: The contrast may carry meaning—white (light, life, celebration) against dark (earth, death, the unknown)

No other colors traditionally—this binary creates visual unity and focuses attention on form rather than chromatic variation.

Modern commercial Warli art sometimes introduces additional colors, though purists consider this dilution of authentic aesthetic.

Recurring Motifs and Themes

Certain images appear repeatedly in Warli painting:

The tarpa dance: The most iconic Warli image shows humans arranged in spiral or circular formation around a central tarpa player (tarpa is a trumpet-like instrument). The figures hold hands, bodies angled to suggest movement—a frozen moment of the communal dance central to Warli festivals.

Symbolic meaning: The dance represents:

- Community unity and collective identity

- Celebration and joy

- Cyclical time (the spiral/circle suggesting eternal return)

- Connection to ancestors (who are believed present during rituals)

- Human harmony and social bonds

Agricultural scenes:

- Plowing with oxen

- Sowing seeds

- Harvesting

- Threshing grain

- Carrying produce

These document Warli livelihood and annual agricultural cycle—art as agricultural calendar and cultural documentation.

Hunting and fishing:

- Hunters with bows and spears pursuing animals

- Fishers with nets or traps

- Dogs assisting hunts

- Forest animals—deer, tigers, birds

Recalling traditional subsistence practices, maintaining memory of forest-dwelling past.

Marriage and celebration:

- Wedding processions

- Bride and groom

- Musicians and celebrants

- Feast preparations

Social occasions demanding artistic commemoration.

Nature:

- Trees bearing fruits

- Animals in natural settings

- Sun and moon

- Mountains and rivers

- Birds in trees

Warli relationship with natural environment.

Palghat (sacred marriage painting): The most important Warli painting traditionally created for weddings, showing the marriage of Palaghata, a fertility deity. This painting:

- Must be created on the wall of the marriage chamber

- Shows the deity surrounded by symbolic elements—trees, animals, geometric patterns

- Invokes blessing and fertility for the couple

- Is ritually consecrated through ceremony

- Remains on the wall until it naturally deteriorates

The Palghat painting connects individual marriage to cosmic and divine principles, positioning human coupling within larger frameworks of fertility, regeneration, and cosmic order.

Materials and Technique

Traditional materials:

Surface: Fresh mud wall, plastered with mixture of:

- Red earth

- Cow dung (which has antiseptic properties and creates smooth finish)

- Water The wall is prepared shortly before painting, creating proper dampness and smoothness.

Paint:

- Ground rice paste mixed with water

- Sometimes gum added as binder

- The paste must be right consistency—too thick won’t flow, too thin won’t be visible

Tools:

- Bamboo stick with one end chewed or split to create brush-like tip

- Sometimes matchsticks

- Occasionally fingers for certain marks

Application method: Artists work freehand, without preliminary sketches, drawing directly with white paste on dark wall. The composition emerges from practiced memory—motifs learned over years, arrangements internalized through repeated observation and creation.

Painting occasion: Traditionally, walls are painted for:

- Weddings (especially the Palghat painting)

- Harvest festivals

- New Year

- Other significant occasions

Who paints: Primarily married women of the household, though men may assist with certain ritual paintings. Young girls learn by observing and practicing simple motifs, gradually mastering complex compositions.

Ephemeral nature: Wall paintings deteriorate naturally—rain, humidity, and time cause them to fade and disappear. This impermanence is accepted; new occasions require fresh paintings. The tradition’s continuity matters more than individual works’ preservation.

Spatial Organization

Warli compositions often fill entire walls with dense arrangements of figures and scenes:

No ground line: Figures don’t stand on a baseline but scatter across the surface, creating all-over composition

Multiple scales: Important figures or elements may be larger, but not according to naturalistic perspective

Narrative simultaneity: Different moments or scenes coexist in single composition

Horror vacui: Every space potentially filled with pattern or figure

Spiral and circular arrangements: Compositions often organize around circular or spiral principles, reflecting the tarpa dance’s centrality

This spatial organization reflects a worldview where:

- Time is cyclical rather than linear

- All life interconnects

- Human activity occurs within, not separate from, natural environment

- Sacred and mundane coexist

Jivya Soma Mashe: From Village to Global Recognition

The transformation of Warli art from local ritual practice to internationally exhibited art owes much to Jivya Soma Mashe (1934-2018).

Born in a small Warli village, Jivya learned painting from his mother and father (unusually, as it’s typically women’s practice). He painted on walls for traditional occasions, working as agricultural laborer for survival.

In the 1970s, he began painting on paper when encouraged by art enthusiasts who recognized his talent. His work came to the attention of the broader art world, leading to:

- Exhibitions in India and internationally

- Padma Shri award (1984), India’s fourth-highest civilian honor

- Commissions for major public murals

- International residencies and exhibitions

- Recognition as master artist rather than mere craftsperson

Jivya’s work maintained traditional Warli visual language while introducing:

- Larger scale compositions

- Increased complexity and detail

- Personal artistic vision within traditional vocabulary

- Experimentation with different surfaces and contexts

His success brought:

- Income and improved living conditions for his family

- Recognition and pride for the Warli community

- Market for other Warli artists’ work

- Documentation and preservation of the tradition

- But also questions about commercialization, authenticity, tradition vs. innovation

Jivya trained numerous younger artists, including his son Balu Mashe, establishing multi-generational artistic lineage that continues evolving the tradition.

Contemporary Practice

Today, Warli art exists in two parallel forms:

Village ritual practice:

- Women continue painting walls for weddings and festivals

- Traditional materials, motifs, and meanings maintained

- Ephemeral works serving ceremonial functions

- Minimal outside attention or commercial involvement

- Authentic continuation of ancient practice

Commercial art market:

- Paper paintings created for sale

- Artists working semi-professionally or full-time

- Sales through galleries, cooperatives, online platforms

- Income supporting families, sometimes substantially

- Adaptations to market preferences (certain subjects more popular)

- Loss of ritual context

- Questions about authenticity when divorced from original function

The relationship between these two forms is complex—neither entirely separate nor fully integrated. Some artists work in both contexts, painting walls for community occasions and paper for sale. The commercial market has incentivized continuation of the tradition, potentially saving it from extinction, but also transformed its nature and meaning.

Bhil Art: Devotional Visions

The Bhil People

The Bhil (or Bheel) are among India’s largest and oldest tribal groups, living across western and central India, with significant populations in Maharashtra’s northern districts.

The name possibly derives from vil (bow), referencing their historical identity as forest hunters and warriors. Bhil oral traditions claim they inhabited these lands since ancient times, predating the arrival of Hindu kingdoms and Aryan migrations.

Pithora Painting: Art as Worship

The most distinctive Bhil artistic tradition in Maharashtra (shared with related groups like the Rathwa) is Pithora painting (also spelled Pithoro).

Religious function: Pithora isn’t decorative art but votive painting—created to fulfill religious vows, propitiate deities, ensure prosperity, or mark major life events.

The Pithora deity: Pithora (or Baba Pithora) is a powerful deity or collection of deities riding horses. Different Bhil sub-groups have varying mythologies, but generally Pithora:

- Protects devotees

- Grants prosperity

- Ensures fertility and good harvests

- Must be periodically honored through elaborate painting ceremonies

When Pithora is painted:

- To fulfill vows made when seeking divine help

- After major life events (weddings, births)

- When misfortune strikes (illness, crop failure, death)

- Periodically to maintain divine favor

The painting ceremony: Creating a Pithora painting isn’t merely artistic work but extended religious ceremony involving the entire community:

- Engaging the badwa: A badwa (priest-shaman-artist) is hired. These specialists possess both ritual knowledge and painting skill, passed through patrilineal lineage.

- Preparatory rituals: The family undergoes purification, fasting, and preparatory ceremonies lasting days.

- Wall preparation: A prominent wall (usually in main room) is plastered and prepared.

- Painting process: The badwa and assistants paint over several days while the family hosts the community with food, music, and celebration.

- Consecration: Once complete, the painting is ritually activated through mantras, offerings, and ceremonies.

- Feast: The event culminates in communal feasting, dancing, and celebration.

- Duration: The entire process can last a week or more.

- Cost: Substantial—families may spend considerable resources, which redistributes wealth within the community.

Pithora Visual Characteristics

Horses dominate: The central deity riding horseback appears prominently, often with multiple horses filling the composition. Horses symbolize:

- Power and mobility

- Royal status of the deity

- Speed and strength

- Sacred vehicles carrying divine presence

Dense, crowded compositions: Unlike Warli’s spare geometry, Pithora paintings are visually dense:

- Every space filled with figures, symbols, patterns

- Horror vacui taken to extreme

- Multiple scales and perspectives coexisting

- Narrative and symbolic elements layered together

Bright, bold colors: Traditionally natural pigments, increasingly synthetic paints:

- Reds and oranges dominate (often from red ochre or sindoor)

- Yellows (from turmeric or ochre)

- Blues (less common traditionally, more available with synthetic paints)

- Greens (from plant sources or modern paints)

- White for highlights and details

- Black for outlines and definition

Symbolic elements:

- Sun and moon: Cosmic order, time

- Trees: Life, fertility, cosmic axis

- Wedding processions: Social celebration, continuity

- Agricultural scenes: Livelihood and prosperity

- Animals: Cattle, elephants, peacocks, tigers—each with symbolic significance

- Geometric patterns: Borders and fillers with ritual meanings

- Stick-like human figures: Similar to Warli but with more variation and detail

- Architectural elements: Houses, temples, gates suggesting cosmic geography

Border patterns: Elaborate decorative borders frame the central imagery, often with repeating geometric motifs—dots, lines, zigzags, triangles creating rhythmic patterns.

Ritual Permanence

Unlike Warli paintings that naturally deteriorate, Pithora paintings are meant to endure as long as the house stands. They’re not repainted or removed but maintained, accumulating power over time. The house becomes a shrine, the wall a permanent sacred object.

If the house is rebuilt or the family moves, a new Pithora must be painted—the divine presence resides in the specific painting on the specific wall, not transferable.

Contemporary Transformations

As with Warli art, Pithora has entered commercial markets:

Paper paintings: Badwas and other Bhil artists now create Pithora-style paintings on paper or cloth for sale, divorced from original ritual context.

Adaptations: Commercial works maintain the dense, colorful aesthetic but lack the spiritual dimension and ceremonial context.

Artist recognition: Some Bhil artists have gained wider recognition, exhibiting nationally and internationally.

Documentation: Anthropologists and art historians have documented traditional Pithora ceremonies before they potentially disappear.

Tensions: The commercialization raises familiar questions—does art maintain authenticity when separated from ritual function? Can sacred imagery become commodity without losing essential meaning?

Other Bhil Arts

Beyond Pithora, Bhil communities practice:

Body decoration: Tattoos (permanent) and painted designs (temporary) adorning women’s faces, arms, and torsos with geometric and floral patterns

Terracotta sculpture: Clay figures of deities, animals, and humans for worship and votives

Basketry and weaving: Creating functional objects with decorative patterns

Beadwork: Elaborate necklaces, bracelets, and ornaments

Wood carving: Decorating doorframes, posts, and household objects

Gond Art: Pattern-Filled Forms

The Gond Tradition

The Gond people, one of India’s largest tribal groups, live primarily in Madhya Pradesh and Chhattisgarh, but significant populations inhabit eastern Maharashtra (Gadchiroli and Chandrapur districts).

Gond art shares characteristics with traditions across their broader geographic range while maintaining regional variations.

Distinctive Style

Pattern filling: The most recognizable Gond characteristic is filling every form with intricate internal patterns:

- Bodies of animals covered in dots, dashes, lines, curves

- Trees filled with rhythmic marks

- Even backgrounds patterned densely

- No empty space—visual horror vacui

Line types:

- Fine parallel lines (hatching)

- Dots arranged in rows or clusters

- Short dashes creating texture

- Curved lines suggesting movement

- Zigzags and waves

- Concentric circles

These patterns create:

- Visual richness and texture

- Sense of movement and energy

- Volume and three-dimensionality despite flat forms

- Mesmerizing rhythmic quality

- Distinctive instantly recognizable aesthetic

Subjects:

- Animals: Tigers, deer, elephants, peacocks, fish, snakes, monkeys

- Trees: Sacred and fruit-bearing trees, often elaborate and fantastical

- Birds: Peacocks especially prominent, also parrots, owls, mythical birds

- Mythological scenes: Stories from Gond oral traditions

- Nature spirits: Deities inhabiting trees, rocks, water

- Human figures: Less common than animals, but present in narrative scenes

- Landscapes: Hills, rivers, forests populated with creatures

Colors: Traditionally earth tones—reds, browns, ochres, blacks, whites from natural sources.

Contemporary Gond art uses vibrant synthetic colors—bright reds, yellows, blues, greens, oranges creating bold chromatic impact.

Cultural Context

Animistic worldview: Gond art expresses belief that spirit forces inhabit natural forms—every tree, rock, animal potentially divine or spiritually significant.

Mythological narratives: Paintings illustrate Gond creation myths, deity stories, ancestral tales—visual renderings of oral traditions.

Ritual function: Traditionally painted on walls during festivals, ceremonies, and life transitions—art serving religious and social functions.

Digna and floor paintings: Besides wall paintings, Gond women create digna—ritualistic floor designs similar to rangoli, using rice flour or colored powders, for festivals and ceremonies.

Jangarh Singh Shyam: Transformative Figure

Jangarh Singh Shyam (1962-2001) transformed Gond art from village walls to international art world, paralleling Jivya Soma Mashe’s impact on Warli art.

Born in a Pardhan Gond family (Pardhans are traditional bards and artists), Jangarh learned painting from his grandfather, a ritual artist creating images for Gond ceremonies.

In the 1980s, artist J. Swaminathan encountered Jangarh and invited him to Bhopal, where he worked at Bharat Bhavan (a multi-arts complex). There, Jangarh began creating paintings on paper and canvas, adapting traditional visual language to new contexts.

His work featured:

- Elaborate compositions filled with patterned forms

- Mythological subjects from Gond traditions

- Brilliant colors and intricate details

- Personal artistic vision within traditional vocabulary

- Experimentation with new materials and scales

Jangarh achieved significant success:

- National and international exhibitions

- Murals for public buildings

- Recognition as contemporary artist, not merely folk craftsperson

- Influence on younger generation of Gond artists

- But also personal struggles with depression

His tragic suicide in 2001 shocked the art world, but his legacy continues through numerous artists he influenced and trained.

Contemporary Gond Art

Today, multiple Gond artists have achieved recognition:

Venkat Raman Singh Shyam: Jangarh’s nephew, continuing and innovating the tradition

Bhajju Shyam: Creating Gond-style illustrated books, including the celebrated “The London Jungle Book”

Durga Bai: Female artist gaining international recognition

Ram Singh Urveti: Known for mythological subjects and elaborate compositions

Gond art has become commercially successful, with:

- Regular gallery exhibitions

- International market presence

- Books and merchandise featuring Gond designs

- Public murals and commissions

- Teaching workshops spreading techniques

This success brings benefits—income, recognition, preservation—but also concerns about commercialization, loss of ritual context, and market pressures homogenizing the work.

Other Maharashtra Tribal Arts

Katkari Art

The Katkari (or Kathodi) people, traditionally semi-nomadic, create:

Wall paintings: Simple geometric designs on temporary dwellings

Tattoos: Permanent body decoration with symbolic patterns

Basketry: Intricate woven baskets and mats with geometric patterns

Functional decoration: Adorning everyday objects with simple carved or painted designs

Their art reflects mobile lifestyle—portable, quickly created, using minimal materials.

Kokna Art

The Kokna communities practice:

Warli-influenced wall paintings: Sharing geographic proximity with Warli, showing stylistic overlap

Rice paste designs: Similar to warli but with regional variations

Ritual paintings: For marriages and festivals

Textile arts: Weaving and embroidery with traditional patterns

Mahadeo Koli Art

The Mahadeo Koli, living in western Maharashtra’s hills, create:

Devotional paintings: Images of deities for household shrines

Votive arts: Objects offered at temples and sacred sites

Body decoration: Painted and tattooed designs, especially for women

Functional objects: Decorated baskets, pottery, tools

Shared Elements Across Traditions

Despite diversity, Maharashtra’s tribal arts share characteristics:

Geometric tendency: Even when depicting recognizable forms, reduction toward geometric essence

Pattern emphasis: Love of repetitive patterns creating texture and rhythm

Ritual function: Art serving religious, ceremonial, social purposes

Communal creation: Often collaborative, involving multiple people

Oral transmission: Knowledge passed through demonstration and practice, not written instruction

Natural materials: Traditionally using locally available pigments, surfaces, tools

Animistic worldview: Reflecting belief in spirit forces inhabiting nature

Ephemeral and permanent: Some traditions emphasize temporary art, others seek permanence

Minimal but meaningful: Working with limited means to create rich significance

Materials and Techniques: Traditional Practices

Surfaces

Mud walls: The primary canvas, prepared by:

- Mixing red earth with cow dung and water

- Applying to walls (usually bamboo or stick framework)

- Smoothing to create paintable surface

- Allowing slight dampness for paint adhesion

Floors: Packed earth or cow-dung-coated floors for temporary designs

Rock faces: Occasionally painted, connecting to ancient rock art traditions

Cloth and hide: Less common, but used for portable paintings or ceremonial objects

Bodies: Skin as surface for painted and tattooed designs

Pigments

Traditional natural sources:

White:

- Ground rice paste

- Lime (calcium hydroxide)

- White clay

Red:

- Red ochre (iron oxide)

- Sindoor (vermillion)

- Red earth

- Certain flowers

Black:

- Charcoal

- Soot from oil lamps

- Burnt rice husk

Yellow:

- Turmeric

- Yellow ochre

- Certain flowers and roots

Green:

- Crushed leaves

- Certain plant extracts

Brown:

- Various earth pigments

- Tree barks

Blue:

- Rare traditionally, occasionally from indigo

- More common with modern synthetic dyes

Binders:

- Gum from trees (especially acacia)

- Plant resins

- Animal glue (rarely)

- Water mixed with pigment

Tools

Application implements:

Bamboo sticks: Chewed or split ends creating brush-like tips

Twigs: Various woods providing different flexibility and line quality

Fingers: Direct application, especially for pattern fills

Cloth wraps: Around fingers or sticks for broader marks

Matchsticks: Modern addition for fine details

Feathers: Occasionally for delicate work

No conventional brushes in traditional practice—the distinctive quality of tribal art partly results from these unconventional tools.

Techniques

Freehand drawing: Most tribal artists work without preliminary sketches, drawing directly from internalized knowledge of motifs and compositions

Repetitive patterning: Filling forms with rhythmic repeated marks—dots, dashes, lines—creating texture and suggesting movement

Flat color application: No modeling or shading—forms rendered in flat colors with pattern providing visual interest

Outlining: Strong outlines define forms, sometimes in contrasting color (especially black)

Horror vacui: Filling available space with pattern, figures, or decorative elements

Symbolic placement: Positioning elements according to meaning and ritual significance rather than naturalistic spatial logic

Symbolism and Meaning

Tribal art’s meanings often remain opaque to outsiders, rooted in specific cultural knowledge:

Common Symbols

Horses: Power, deity vehicles, royalty, mobility, martial strength

Tigers: Fierce power, forest spirits, danger and protection

Peacocks: Beauty, pride, rain (associated with monsoon), connection to divine

Fish: Fertility, abundance, water as life source

Snakes: Powerful spirits, both dangerous and protective, earth forces, transformation

Trees: Life, fertility, cosmic axis connecting earth and sky, specific trees sacred to specific deities

Sun and Moon: Cosmic order, time’s passage, male and female principles

Geometric patterns: Often carry meanings lost or partially remembered—some protective, some auspicious, some purely decorative

Spirals and circles: Cyclical time, eternal return, cosmic wholeness, dance and community

Triangles: Depending on orientation—male/female, mountains, stability

Dots and lines: May represent stars, seeds, rain, or purely decorative elements

Ritual Meanings

Many tribal paintings serve specific ritual functions:

Invoking divine presence: Images make deities present and accessible

Protection: Certain patterns and images ward off evil spirits, disease, misfortune

Fertility: Symbols ensuring human, animal, and agricultural fertility

Prosperity: Images inviting wealth, good harvests, abundance

Life transitions: Marking births, marriages, deaths with appropriate imagery

Seasonal observances: Paintings for festivals marking agricultural calendar

Ancestor connection: Some images invoke or honor ancestors

Healing: Certain paintings created during illness to invoke healing powers

Cultural Knowledge

Understanding tribal art’s deeper meanings requires:

Oral traditions: Myths, stories, songs explaining symbols and their significance

Ritual participation: Experiencing ceremonies where art appears in context

Community membership: Insider knowledge not readily shared with outsiders

Linguistic understanding: Many meanings embedded in tribal languages, difficult to translate

Much symbolic knowledge has been lost or partially forgotten as traditions erode, languages disappear, and younger generations adopt mainstream culture.

Contemporary Challenges and Transformations

Threats to Tradition

Cultural assimilation:

- Education system emphasizing mainstream culture

- Media promoting non-tribal values and aesthetics

- Migration to cities breaking community bonds

- Younger generations seeing tribal identity as backward

Economic pressure:

- Poverty pushing people away from traditional livelihoods

- Time spent on art-making often unremunerative

- Commercial work may pay more than traditional practices

Environmental change:

- Deforestation reducing access to traditional materials

- Forest laws restricting gathering of natural pigments

- Land alienation separating communities from sacred sites

- Climate change affecting agricultural calendar and rituals

Loss of ritual context:

- Ceremonies performed less frequently

- Younger people lacking knowledge of traditional practices

- Conversion to mainstream Hinduism or other religions changing beliefs

- Urbanization breaking down village-based communal structures

Knowledge erosion:

- Elders dying without fully transmitting knowledge

- Oral traditions fading

- Symbolic meanings forgotten

- Ritual specialists (like badwas) becoming rare

Opportunities and Adaptations

Commercial markets:

- Urban Indian and international buyers interested in tribal art

- Income supporting artists and families

- Economic incentive for continuation

Cultural recognition:

- Government awards and recognition (Padma Shri to tribal artists)

- Museum exhibitions

- Academic study and documentation

- Media attention

Art world acceptance:

- Tribal artists exhibited alongside contemporary artists

- Recognition as valid aesthetic achievement, not mere craft or ethnographic curiosity

- Gallery representation

- Critical appreciation

Education and training:

- Workshops teaching traditional techniques

- Craft centers supporting artists

- Apprenticeships with master artists

- Some schools incorporating tribal art into curriculum

Tourism:

- Cultural tourism bringing visitors to tribal areas

- Demonstrations and sales opportunities

- But also risks of commodification and cultural appropriation

Digital platforms:

- Online sales expanding markets

- Social media giving artists direct audience

- Documentation preserving practices digitally

- Virtual exhibitions

NGO support:

- Organizations working to preserve traditions

- Fair trade ensuring better compensation

- Collective organizing giving artists negotiating power

- Cultural documentation projects

Authenticity Questions

The commercialization of tribal art raises complex questions:

Can sacred art become commodity without losing essential meaning? Does a Pithora painting on paper for sale retain any connection to its ritual origins?

Who benefits from tribal art sales? Are artists fairly compensated, or do middlemen and galleries extract most profit?

Does market success preserve or destroy tradition? Income incentivizes continuation, but market demands may pressure artists toward repetitive, commercially viable work rather than authentic cultural practice.

What is “authentic” tribal art? Is innovation acceptable, or must art remain frozen in idealized traditional forms? Who decides?

Cultural appropriation: When non-tribal people create “Warli-style” or “Gond-style” art, is this appreciation or appropriation? Should tribal aesthetic vocabularies be protected as intellectual property?

Loss of context: Art removed from ritual, ceremonial, or community context becomes decoration—is this preservation or transformation into something fundamentally different?

These questions lack simple answers, requiring ongoing negotiation between preservation, economic necessity, cultural respect, and artistic evolution.

Significance and Legacy

What Tribal Art Represents

Cultural continuity: Living links to ancient past, maintaining practices across millennia

Alternative aesthetics: Visual languages developed independently from mainstream Indian and Western art traditions

Worldview expression: Embodying tribal understandings of cosmos, nature, divine, human place in larger order

Community identity: Marking and reinforcing tribal distinctiveness within diverse Indian society

Resistance: Maintaining cultural practices despite pressures toward assimilation

Creativity within constraints: Achieving richness with minimal materials and techniques

Integration of life and art: Art inseparable from religion, social organization, economic activity, daily existence

Women’s creativity: Many traditions giving women cultural authority and creative outlet

Environmental relationship: Reflecting sustainable, respectful relationships with natural world

Human universals: Expressing through specific cultural forms the universal human impulse toward beauty, pattern, meaning, sacred expression

Influence and Legacy

Maharashtra’s tribal arts have influenced:

Contemporary Indian art: Modern artists drawing inspiration from tribal aesthetics—simplification, pattern, bold color

Design and commercial art: Tribal motifs appearing in fashion, home decor, advertising (raising appropriation concerns)

Cultural pride: Both tribal and broader Indian recognition of indigenous artistic achievement

Tourism: Contributing to Maharashtra’s cultural tourism economy

Academic study: Anthropologists, art historians, folklorists documenting and analyzing traditions

Global art world: International exhibitions and collections including tribal art

Social movements: Tribal arts sometimes mobilized for political and social advocacy

Future Prospects

The future of Maharashtra’s tribal arts remains uncertain:

Pessimistic scenario: Continued cultural erosion, loss of ritual contexts, reduction to commercial commodity, eventual disappearance except as museum relics and historical curiosities

Optimistic scenario: Successful adaptation combining commercial viability with cultural authenticity, economic support enabling continuation, younger generations valuing and maintaining traditions, creative evolution while maintaining essential character

Most likely: Something between—continued practice but with significant transformations, some traditions thriving while others fade, ongoing negotiations between preservation and innovation, commercial and ritual contexts coexisting tensely

What seems certain is that these traditions won’t remain static. They’ll evolve, adapt, transform—as they always have. The question is whether that evolution maintains living connection to their origins and meanings, or whether commercialization and cultural change sever those roots, leaving beautiful but ultimately hollow aesthetic forms.

Conclusion: Lines in Earth, Patterns in Time

When a Warli woman traces white rice paste figures on her mud wall, when a Bhil badwa paints Pithora on horseback surrounded by cosmic symbols, when a Gond artist fills animal forms with intricate patterns—they participate in traditions extending back through time beyond historical documentation, maintained through oral transmission and bodily practice, connecting present to ancestors, individual to community, human to natural and divine.

These arts speak in visual languages developed over millennia, refined through countless iterations, tested by time and use, proven adequate to their purposes. They’re simultaneously specific to their communities and universal in their human creativity, local in their materials and meanings yet global in their aesthetic power.

The geometric simplicity of Warli figures, the bold colors of Pithora paintings, the pattern-filled richness of Gond art—these represent distinct tribal identities, different ways of seeing and marking the world, alternative aesthetic philosophies to mainstream traditions. They remind us that beauty takes many forms, that sophistication doesn’t require realistic representation, that meaning can be carried in the simplest lines and shapes, that art serves purposes far beyond decoration.

As these traditions face uncertain futures, pulled between preservation and innovation, ritual and commerce, community practice and individual artistry, they continue telling stories older than cities, painting symbols whose meanings echo back to humanity’s earliest artistic expressions, maintaining practices that connect modern people to their ancient forbears who also painted on walls, filled surfaces with pattern, invoked divine forces through images, and transformed ordinary materials into vessels of meaning, beauty, and sacred power.

The ancient tribal arts of Maharashtra survive not as museum curiosities but as living traditions—evolving, adapting, sometimes struggling, but continuing to speak in their unique visual languages, continuing to mark space and time with pattern and color and meaning, continuing to assert that these ways of seeing and making and being remain valid, valuable, and vital in a rapidly changing world that too easily dismisses as primitive what is actually profoundly sophisticated, as simple what is actually richly complex, as past what remains vibrantly, stubbornly, beautifully present.