Table of Contents

Introduction to Tanjore Painting

What Is Tanjore (Thanjavur) Painting?

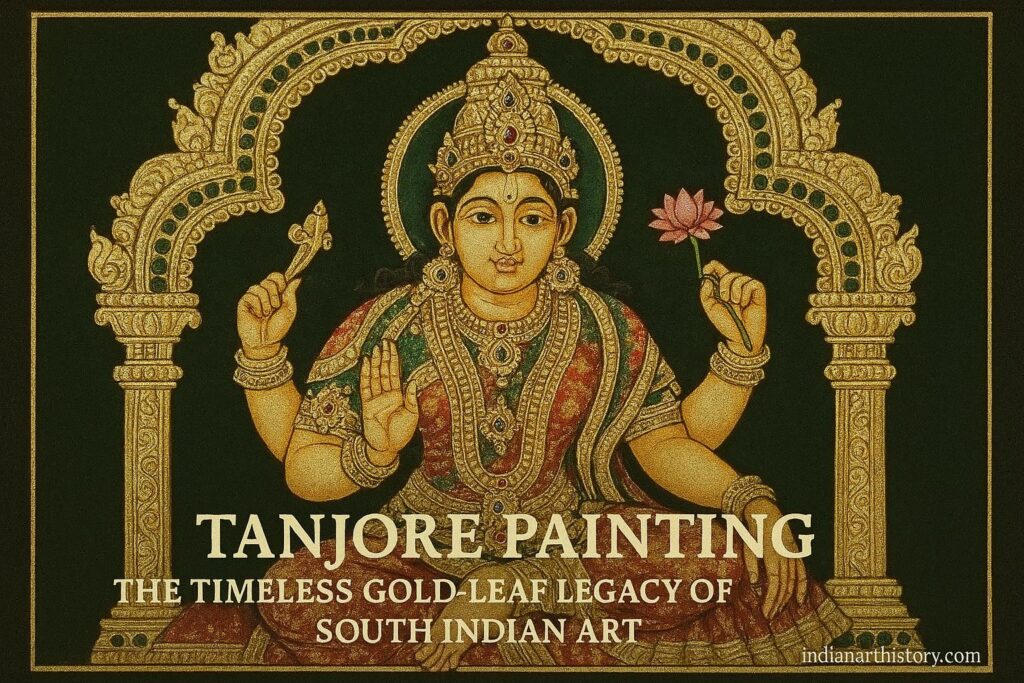

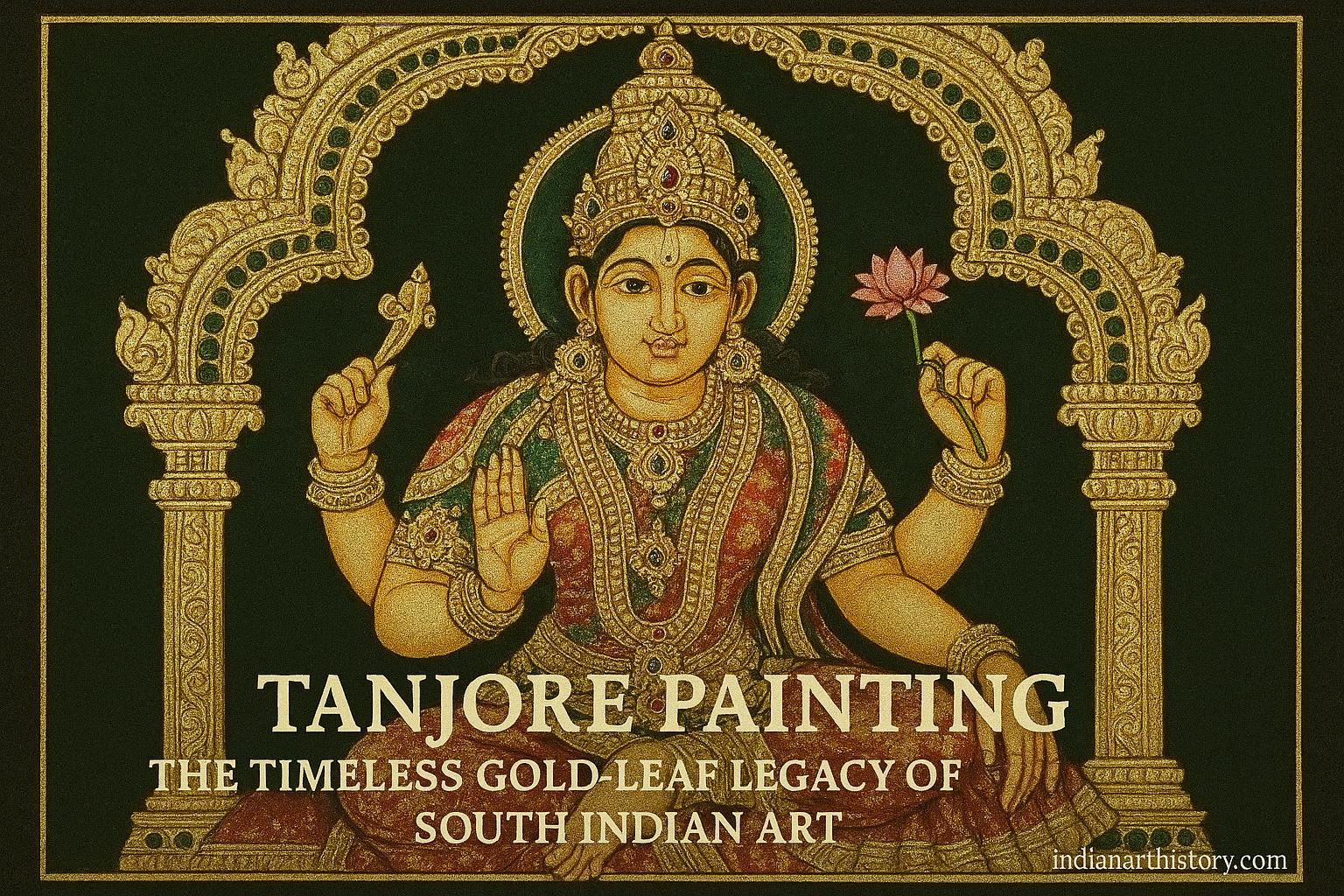

Tanjore painting represents one of India’s most celebrated classical art forms, originating from the temple town of Thanjavur in Tamil Nadu. This distinctive style is immediately recognizable by its rich use of gold foil, vibrant colors, and embossed relief work that creates a three-dimensional effect. Unlike other Indian painting traditions, Tanjore paintings combine the visual splendor of precious materials with deep spiritual significance, making them both artistic masterpieces and devotional objects.

The art form takes its name from Thanjavur (anglicized as Tanjore), a city that served as the cultural capital of South India for centuries. Each painting is a labor-intensive creation that can take weeks or even months to complete, involving multiple layers of preparation, embossing, gilding, and coloring. The result is a luminous work of art that seems to glow with an inner light, capturing the divine presence of the deities depicted within.

Why Tanjore Painting Is Considered a Royal Art Form

The designation of Tanjore painting as a “royal art form” is not merely honorific but reflects its historical origins and patronage. For centuries, these paintings were commissioned exclusively by royalty, wealthy patrons, and temples, making them inaccessible to common people. The use of expensive materials like gold leaf, semi-precious stones, and rare pigments required substantial financial resources, while the technical expertise demanded years of training under master artists.

Royal courts of the Nayakas and Marathas maintained dedicated workshops where skilled artisans created these paintings for palace halls, private chambers, and royal gifts. The iconography itself reflected regal aesthetics, with deities adorned in elaborate jewelry and royal attire, often depicted in darbar (court) settings. This association with royalty elevated the art form’s status and established standards of excellence that continue to define authentic Tanjore paintings today.

Global Recognition and Cultural Importance

In the contemporary art world, Tanjore painting has transcended its regional origins to achieve international recognition. Museums across Europe, America, and Asia feature these works in their collections, recognizing them as significant examples of Indian artistic heritage. The Indian government awarded Tanjore painting a Geographical Indication (GI) tag in 2007, providing legal protection and acknowledging its cultural importance.

Beyond museums and galleries, Tanjore paintings have found homes in diplomatic offices, corporate collections, and private residences worldwide. They serve as cultural ambassadors, introducing global audiences to South Indian aesthetics and Hindu iconography. The art form’s ability to maintain its traditional character while adapting to contemporary spaces demonstrates its enduring relevance and universal appeal.

Historical Origins of Tanjore Painting

Birth of Tanjore Painting in Thanjavur, Tamil Nadu

The genesis of Tanjore painting as a distinct art form can be traced to the 16th century in Thanjavur, though its roots extend deeper into South Indian artistic traditions. The city’s strategic importance as a religious and political center created the perfect environment for artistic innovation. Temple walls already displayed magnificent frescoes, and the arrival of new ruling dynasties brought fresh artistic influences that would eventually coalesce into the Tanjore style.

The geographical location of Thanjavur, with access to trade routes and proximity to other cultural centers, facilitated the exchange of artistic ideas and materials. Artisans who had previously worked on temple murals and manuscript illustrations began experimenting with portable panel paintings, creating devotional images that could be installed in homes and smaller shrines. This shift from wall-based to portable art marked a crucial development in the evolution of Tanjore painting.

Role of the Chola Dynasty in Early Development

While the Chola dynasty’s golden age predates the formal establishment of Tanjore painting, the aesthetic foundations laid during their rule proved instrumental. The Cholas were renowned patrons of art and architecture, constructing magnificent temples adorned with bronze sculptures and murals. The principles of proportion, iconography, and composition developed during this period influenced subsequent artistic traditions in the region.

Chola bronzes, with their graceful proportions and detailed ornamentation, provided visual templates that Tanjore painters would later adapt. The emphasis on capturing divine beauty through idealized forms, the attention to jewelry and costume details, and the practice of following scriptural guidelines for depicting deities all originated in this earlier period. Though Tanjore painting as we know it emerged later, it inherited and refined these Chola aesthetic principles.

Influence of the Nayakas and Maratha Rulers

The true flourishing of Tanjore painting began under the Nayaka rulers (1532-1673) and reached its apex during the Maratha period (1676-1855). The Nayakas, who established Thanjavur as their capital, were ardent devotees and generous patrons of the arts. They commissioned numerous paintings for temples and palaces, encouraging artists to develop techniques that would distinguish their work from other regional styles.

The Marathas, particularly Raja Serfoji II, brought new dimensions to Tanjore painting. Having experienced the artistic traditions of Maharashtra and exposure to European art through colonial contacts, they encouraged experimentation while maintaining the art form’s essential character. This period saw refinements in gold application techniques, the introduction of glass-bead embellishments, and expanded thematic repertoires that included secular subjects alongside religious imagery.

Temple Culture and Royal Patronage

The symbiotic relationship between temple culture and royal patronage created the ecosystem in which Tanjore painting thrived. Temples were not merely places of worship but centers of cultural production, housing dancers, musicians, and visual artists. Kings expressed their devotion and legitimized their authority through temple construction and embellishment, with paintings serving as offerings to the deities.

Royal workshops operated under the direct supervision of court officials, ensuring quality control and maintaining artistic standards. Master painters received stipends, land grants, and honors, securing their economic stability and encouraging them to train successors. This institutional framework preserved technical knowledge and iconographic traditions across generations, creating a continuity that sustained the art form through political upheavals and economic changes.

Religious and Spiritual Foundations

Connection with Hindu Bhakti Tradition

Tanjore painting emerged during the height of the Bhakti movement in South India, a devotional revolution that emphasized personal connection with the divine. The paintings served as focal points for this devotion, providing visual access to deities for worshippers who might never enter a temple’s inner sanctum. The radiant gold surfaces were understood not merely as decoration but as manifestations of divine light and presence.

The Bhakti poets and saints, whose compositions formed the soundtrack of South Indian devotion, influenced the emotional tenor of these paintings. Deities were depicted not in remote majesty but with attributes that invited intimate worship—gentle expressions, graceful gestures, and compositions that seemed to acknowledge the devotee’s gaze. This accessibility aligned with Bhakti philosophy, which taught that sincere devotion mattered more than ritual purity or social status.

Role of Temples and Ritual Worship

Temples provided both inspiration and practical requirements for Tanjore paintings. The iconography followed agamic texts that prescribed how deities should be depicted, ensuring theological accuracy. Paintings created for temple use often replicated the forms of the main deity, allowing devotees to perform worship rituals before the image when direct access to the sanctum was restricted.

The ritual context influenced artistic choices in fundamental ways. Gold symbolized the sacred fire that purifies offerings, while the permanence of materials reflected the eternal nature of the divine. The elevated, frontal compositions facilitated darshan—the auspicious act of seeing and being seen by the deity. Even the frame’s architectural elements echoed temple architecture, creating a miniature shrine that sanctified domestic spaces.

Tanjore Paintings as Objects of Devotion

Unlike secular artworks created primarily for aesthetic appreciation, Tanjore paintings functioned as active participants in religious life. Families performed daily worship before these images, offering flowers, incense, and prayers. The paintings were consecrated through rituals that invoked divine presence, transforming them from representations into embodiments of sacred power.

This devotional function shaped conservation practices and transmission patterns. Paintings passed through families as heirlooms, accumulating spiritual value through generations of worship. The act of commissioning a painting itself was considered meritorious, with patrons believing that creating sacred images earned religious merit. This understanding of Tanjore paintings as spiritual tools rather than mere decorations explains their enduring significance in Hindu households.

Evolution of Tanjore Painting Over Centuries

Early Traditional Phase

The formative period of Tanjore painting established its fundamental characteristics. Early works displayed strong connections to mural painting traditions, with compositions often adapted from temple walls. Artists worked primarily on wooden panels prepared with layers of cloth and limestone paste, creating smooth surfaces suitable for detailed work. The color palette drew from natural mineral sources, producing the characteristic deep reds, blues, and greens that distinguish traditional pieces.

During this phase, iconographic conventions solidified based on shilpa shastra texts and local traditions. The deity always occupied the central position, rendered larger than accompanying figures to emphasize divine status. Compositional elements—the arch framing the figure, the throne or pedestal, attendant figures, and decorative borders—became standardized, creating a visual grammar that viewers could immediately recognize as distinctively Tanjore.

Maratha Period Innovations

The Maratha era witnessed significant technical and aesthetic developments. Artists refined the gesso relief technique, creating more elaborate embossing that added dramatic three-dimensionality to jewelry, crowns, and decorative elements. The use of gold became more lavish and sophisticated, with artisans developing methods to apply it in patterns that enhanced the play of light across the painting’s surface.

This period also saw stylistic borrowings from other traditions. Maratha rulers, familiar with painting styles from their ancestral regions, encouraged fusion elements. The result was a more ornate aesthetic without abandoning core principles. New themes emerged, including portraits of rulers depicted in divine iconographic formats, coronation scenes, and elaborate darbar compositions that celebrated royal grandeur while maintaining the art form’s spiritual essence.

Colonial Era Challenges

The colonial period brought existential challenges to Tanjore painting. The decline of indigenous royal courts eliminated the primary patronage system that had sustained artists for generations. British administrators and European collectors showed interest in Indian art, but their preferences often favored miniature paintings and other styles deemed more refined or portable. The economic pressures of colonial rule made the expensive materials required for authentic Tanjore painting increasingly inaccessible.

Many traditional artists abandoned their craft, seeking other livelihoods as demand evaporated. Those who continued often compromised on materials and techniques, producing works that lacked the quality of earlier periods. The knowledge transmission system began breaking down as fewer students entered training and master artists passed away without documented successors. By the early 20th century, Tanjore painting seemed destined for extinction, surviving primarily in temple collections and wealthy households.

Modern Revival and Contemporary Adaptations

The post-independence period brought renewed attention to traditional Indian arts as expressions of national identity. Government initiatives, cultural organizations, and individual advocates worked to revive Tanjore painting. Workshops reconnected elderly masters with new students, documenting techniques that might otherwise have been lost. Art schools incorporated Tanjore painting into curricula, providing institutional support and contemporary relevance.

Today’s Tanjore painting exists in multiple forms. Purists maintain traditional techniques and subjects, creating works indistinguishable from historical pieces. Contemporary artists experiment with secular subjects, modern color palettes, and innovative compositions while retaining signature elements like gold work and embossing. Commercial producers create affordable versions using synthetic materials, making the aesthetic accessible to middle-class buyers. This diversity ensures vitality while raising questions about authenticity and artistic integrity.

Distinctive Characteristics of Tanjore Painting

Rich Use of Gold Foil

The most immediately striking feature of Tanjore painting is its abundant gold application. Unlike other Indian painting traditions that use gold sparingly for accents, Tanjore paintings employ 22-carat gold foil across large areas—adorning jewelry, crowns, decorative borders, and sometimes entire garments or backgrounds. This lavish use of gold creates a luminous quality that distinguishes the art form and justifies its reputation as India’s most opulent painting tradition.

The gold serves multiple purposes beyond mere decoration. Technically, it provides a reflective surface that animates the painting under changing light conditions, creating an almost three-dimensional effect. Symbolically, gold represents purity, divinity, and the radiant nature of sacred beings. Economically, it demonstrates the patron’s devotion and resources, transforming each painting into a form of treasure as well as art.

Bold Colors and Flat Perspective

Tanjore paintings employ a bold, saturated color palette that prioritizes symbolic meaning over naturalistic representation. Primary colors dominate—deep reds symbolizing power and auspiciousness, vibrant blues associated with divine transcendence, rich greens representing fertility and prosperity. These colors are applied in flat, unmodulated areas without shading or gradation, creating a decorative rather than realistic effect.

The compositional approach favors frontality and two-dimensionality over perspective depth. Background elements are compressed into decorative patterns rather than receding into space. This flatness aligns with the devotional purpose—the deity faces the viewer directly, facilitating darshan without compositional distractions. The lack of naturalistic space emphasizes the painting’s role as a sacred icon rather than a window into physical reality.

Stylized Figures and Iconography

Figures in Tanjore paintings follow strict iconographic conventions rather than naturalistic observation. Deities are rendered according to proportional canons specified in ancient texts, with measurements relating to face length determining body dimensions. Features are idealized—large lotus-petal eyes, refined noses, small mouths—creating an otherworldly beauty that distinguishes divine beings from mortals.

The stylization extends to postures and gestures. Deities typically stand in tribhanga (triple-bend) poses that convey graceful movement within static compositions. Hand gestures (mudras) communicate specific meanings—blessing, fearlessness, teaching—that informed viewers can decode. Attributes and vehicles associated with each deity appear in prescribed arrangements, allowing identification even when names are absent.

Ornamental Borders and Decorative Motifs

The elaborate borders framing Tanjore paintings constitute artworks in themselves. These borders feature intricate patterns—paisley motifs, floral scrollwork, geometric designs—executed with gold and vibrant colors. The borders create architectural frames that separate sacred space within the painting from the profane world outside, much as temple walls demarcate consecrated ground.

Decorative elements fill every available space, creating a horror vacui effect characteristic of many Indian artistic traditions. Floral patterns, celestial beings, auspicious symbols, and architectural details surround the central deity. This abundance reflects cosmic plenitude and divine generosity while demonstrating the artist’s technical virtuosity. The overall effect is one of overwhelming richness that befits the depiction of divine beings.

Themes and Subject Matter

Hindu Deities in Tanjore Paintings

Hindu gods and goddesses form the overwhelming majority of subjects in traditional Tanjore paintings. These depictions follow established iconographic traditions that allow viewers to identify deities through attributes, postures, and accompanying symbols. The paintings don’t merely represent these beings but are understood to embody their presence, transforming the artwork into a conduit for divine grace.

The selection of deities for depiction often reflects regional devotional preferences and family traditions. Vaishnava households favor Vishnu and his avatars, while Shaivite families commission images of Shiva and Parvati. The goddess traditions find expression in paintings of Lakshmi, Saraswati, and Durga. This diversity within unity—different deities sharing common stylistic language—demonstrates Hinduism’s inclusive theological framework.

Popular Gods: Krishna, Rama, Lakshmi, Ganesha

Certain deities appear with exceptional frequency in Tanjore painting, reflecting their popularity in South Indian devotion. Krishna, particularly in his butter-thief and flute-player manifestations, embodies divine charm and playfulness. Paintings depict him in various episodes—dancing on the serpent Kaliya, lifting Mount Govardhan, or standing in graceful tribhanga pose playing his flute.

Rama, the ideal king and exemplar of dharma, appears in coronation scenes, forest exile narratives, or family groupings with Sita and Lakshmana. Lakshmi, goddess of prosperity, is frequently commissioned for homes and businesses, often depicted standing on a lotus, distributing wealth from her hands. Ganesha, the remover of obstacles, begins many painting sequences and appears in numerous poses—dancing, sitting, or standing—always recognizable by his elephant head and benevolent expression.

Saints, Mythological Scenes, and Episodes

Beyond single-deity portraits, Tanjore paintings encompass narrative compositions depicting episodes from epics and puranas. The Ramayana and Mahabharata provide endless subject matter—Rama’s coronation, Krishna’s cosmic dance, Durga slaying the buffalo demon. These narrative works allow artists to display compositional skills, incorporating multiple figures and architectural settings while maintaining the art form’s characteristic aesthetic.

South Indian saints and poet-saints also receive representation, particularly the Alvars and Nayanars whose hymns form the devotional soundtrack of Tamil culture. These paintings often show saints in ecstatic worship before their chosen deities, modeling the devotional relationship that patrons hope to achieve. Such works connect the art form to the lived religious culture of Tamil Nadu, bridging ancient mythology and historical devotion.

Symbolism in Gestures, Objects, and Expressions

Every element in a Tanjore painting carries symbolic weight. Hand gestures communicate specific meanings—the abhaya mudra (raised palm) offers protection, the varada mudra (downturned palm) grants boons. Objects held in multiple hands identify deities and their powers—Vishnu’s conch, discus, mace, and lotus; Shiva’s trident and drum; Lakshmi’s lotus flowers.

The inclusion of vehicles (vahanas) adds another layer of meaning. Ganesha’s mouse represents the conquest of egotism, Durga’s lion embodies fearless power, and Vishnu’s eagle Garuda symbolizes the soul’s aspiration toward the divine. Even seemingly decorative elements carry significance—the makara (sea creature) represents fertility and auspiciousness, while the kirtimukha (face of glory) wards off negative forces. Understanding this symbolic vocabulary transforms viewing Tanjore paintings from aesthetic appreciation to reading visual scripture.

Materials Used in Traditional Tanjore Painting

Wooden Plank Base (Jackfruit or Teak Wood)

The foundation of every authentic Tanjore painting is a carefully selected wooden panel. Jackfruit wood was traditionally preferred for its density, smooth grain, and resistance to warping and insect damage. The wood must be properly seasoned, often for years, to ensure dimensional stability. Panels are cut to size according to the intended composition, with larger works requiring joinery techniques to create seamless surfaces from multiple boards.

Teak wood serves as an alternative, prized for its durability and natural oils that repel moisture and pests. The wood selection proves crucial to the painting’s longevity—inferior materials can warp, crack, or deteriorate, destroying the artwork built upon them. Master artists can identify appropriate wood by grain pattern, density, and sound when tapped, knowledge acquired through decades of experience and passed through apprenticeship traditions.

Cotton Cloth and Limestone Paste (Gesso Work)

After preparing the wooden base, artists stretch cotton cloth across the panel’s surface, adhering it with natural adhesives. This cloth layer provides a flexible intermediate surface that accommodates wood movement while offering a suitable substrate for subsequent layers. The cloth must be stretched taut without wrinkles, as any irregularities will telegraph through the final painting.

The next crucial step involves applying multiple coats of limestone paste mixed with Arabic gum or hide glue, creating a gesso ground. This preparation, similar to techniques used in European panel painting, provides a smooth, brilliant white surface for painting while enabling the distinctive embossed relief work. The paste is built up in specific areas—jewelry, crowns, garment borders—to create three-dimensional effects that will later be gilded. Achieving the proper consistency and thickness requires considerable skill, as too-thin applications won’t hold relief details while too-thick layers may crack.

22-Carat Gold Foil

The gold used in traditional Tanjore paintings is genuine 22-carat gold leaf, beaten to extreme thinness. This purity choice balances malleability with durability—24-carat gold is too soft and prone to tearing, while lower karats lack the characteristic color and luster. The gold arrives in thin sheets protected between tissue papers, requiring careful handling as even breath can disturb these delicate leaves.

Application demands specialized tools and techniques. The gesso relief areas receive adhesive sizing, and gold leaf is carefully laid over these areas, conforming to the raised surfaces. Excess gold is removed with soft brushes, and the gilded surfaces are sometimes burnished with agate tools to enhance brilliance. The gold application process can consume days or weeks for elaborate compositions, with artists working in conditions free from drafts and dust that might damage the fragile material.

Natural and Mineral Pigments

Traditional Tanjore paintings employ pigments derived from natural minerals and organic sources. Red comes from vermillion (mercury sulfide) or red ochre, blue from lapis lazuli or indigo, yellow from orpiment or turmeric, green from verdigris or combinations of other pigments. These natural colors produce the characteristic depth and luminosity of authentic works, aging gracefully rather than fading like synthetic alternatives.

Pigments are ground to fine powder and mixed with binding media—gum arabic, egg tempera, or hide glue—creating paint that adheres permanently to the gesso surface. The preparation of colors itself constitutes a specialized skill, as different pigments require different grinding times and binding ratios to achieve optimal consistency and covering power. Many traditional artists prepare their own colors, maintaining recipes passed through family lineages and adjusting formulations based on specific requirements.

Step-by-Step Technique of Making a Tanjore Painting

Preparing the Wooden Board

The creation process begins with selecting and preparing the wooden panel. The seasoned wood is smoothed with progressively finer abrasives until the surface achieves perfect flatness and smoothness. Any knots, cracks, or imperfections must be filled and sanded. The panel’s edges are beveled or shaped according to the intended framing style.

Once surface preparation is complete, the cotton cloth is cut slightly larger than the panel and soaked to remove sizing and impurities. The cloth is then stretched across the wooden surface while still damp, adhering it with natural glue. Artists work from the center outward, eliminating air bubbles and ensuring uniform adhesion. Excess cloth is trimmed after drying, and the edges are sealed to prevent lifting.

Sketching the Outline

With the prepared ground ready, the artist creates a preliminary drawing. Traditional methods employ charcoal or chalk that can be easily corrected. The composition is carefully planned, with the deity’s proportions calculated according to canonical measurements. The central figure is positioned first, followed by surrounding elements—throne or pedestal, architectural framing, decorative borders, and any subsidiary figures.

Some artists use pouncing techniques, transferring designs from perforated paper patterns by dusting with charcoal powder. This method ensures accuracy when replicating established iconographic forms. Others sketch freehand, demonstrating their mastery of proportional systems and compositional principles. Once satisfied with the drawing, artists may reinforce outlines with permanent ink or thin paint, creating guidelines that will survive subsequent layers.

Embossing with Gesso Relief

The distinctive three-dimensional quality of Tanjore painting emerges during the gesso relief phase. Artists prepare limestone paste to thick consistency and apply it to areas designated for gold—jewelry, crowns, garment borders, architectural elements. Using spatulas, small brushes, and specialized tools, they build up relief surfaces that can rise several millimeters above the base level.

Detail work at this stage determines the final richness of the gilded areas. Artists create patterns in the wet gesso—floral motifs on crowns, chain links in necklaces, textile patterns on clothing. Some embed semi-precious stones or glass beads into the gesso, creating additional highlights. The relief work must dry completely before proceeding, a process that can take several days depending on thickness and atmospheric conditions.

Applying Gold Leaf

Gold application represents the most delicate and dramatic transformation in the painting process. The relief areas receive adhesive sizing that remains tacky, providing the grip needed for gold leaf adherence. Artists lift individual gold sheets with special tools or static-charged brushes, positioning them carefully over sized areas. The gold conforms to the relief contours, creating a continuous metallic surface.

Once positioned, gold is gently pressed into place with soft brushes or cotton pads, ensuring complete contact with the adhesive. Excess gold extending beyond sized areas is carefully removed and preserved for future use. Some artists apply multiple gold layers for enhanced brilliance, while others use single applications. After the adhesive cures, burnishing with agate stones compresses the gold and increases its reflective qualities, creating the characteristic luminosity of finished Tanjore paintings.

Coloring and Final Detailing

With gilding complete, artists begin painting the non-gilded areas. Backgrounds receive their base colors first, followed by the deity’s flesh tones, garments, and surrounding elements. The flat application style means colors are laid down in uniform areas without modeling or shading. Borders receive intricate patterns executed with fine brushes, often incorporating gold paint to complement the gold leaf areas.

Final details include facial features, which receive special attention as they convey the deity’s character and emotional presence. Eyes are outlined with precision, expressions refined through subtle adjustments to mouth and brow. Decorative elements—flowers, celestial beings, auspicious symbols—fill remaining spaces. Some artists add final gold accents using gold paint for areas too small or complex for leaf application. The completed painting is then allowed to cure completely before framing and, if intended for worship, consecration through appropriate rituals.

Iconography Rules in Tanjore Painting

Canonical Proportions of Deities

Tanjore painting follows strict proportional systems derived from shilpa shastra texts that codify sacred art. The deity’s face serves as the basic unit of measurement, with total height typically ranging from seven to nine face lengths depending on the specific tradition. The body is divided into sections with specified ratios—the distance from hairline to chin equals the distance from chin to breast, from breast to navel, and so forth.

These proportions create idealized figures that transcend human anatomy, embodying divine perfection. Different deities may receive slight variations—Krishna often appears more youthful and slender, while Ganesha’s proportions accommodate his distinctive elephant head and rotund body. Mastering these measurements requires years of training, as artists must internalize the systems sufficiently to apply them naturally without constant reference to texts.

Facial Features and Body Posture

Divine faces in Tanjore painting display characteristic features that distinguish them from mortal representations. Eyes are large, shaped like lotus petals, extending toward the temples. The nose is refined and straight, the mouth small with a subtle smile suggesting benevolent grace. Eyebrows arch gracefully, and the face overall maintains perfect symmetry. These idealized features create beauty that inspires devotion while maintaining recognizability across different artists and periods.

Body postures follow established conventions. The tribhanga (triple-bend) stance—flexion at neck, waist, and knee—suggests graceful movement within a static composition. Deities in meditation assume lotus posture with perfect symmetry. Standing figures distribute weight according to prescribed formulas. These postural rules ensure that paintings conform to devotional expectations while maintaining the visual harmony essential to sacred art.

Hand Gestures (Mudras)

Hand gestures constitute a sophisticated symbolic language in Tanjore painting. The abhaya mudra—right hand raised, palm outward—signals fearlessness and divine protection. The varada mudra—right hand lowered, palm outward—represents blessing and boon-granting. The dhyana mudra—hands resting in lap—indicates meditation. The jnana mudra—thumb and forefinger touching—symbolizes wisdom and teaching.

Deities with multiple arms display combinations of mudras and held objects, creating complex symbolic statements. Each hand position has been precisely defined through centuries of iconographic development, and deviations from standard forms would be immediately recognized by knowledgeable viewers as errors or innovations. Artists must master not just the physical forms of these gestures but their meanings and appropriate contexts.

Placement of Symbols and Attributes

Each deity carries specific attributes that enable identification and communicate divine powers. Vishnu holds conch, discus, mace, and lotus in his four hands, each symbolizing different aspects of cosmic maintenance. Shiva displays trident, drum, flame, and blessing gesture, representing destruction, creation, and grace. Lakshmi holds lotus flowers and displays varada mudra, embodying prosperity and generosity.

The positioning of these attributes follows rules as strict as proportional canons. Certain objects appear in specific hands—the conch always in Vishnu’s lower left hand, the discus in upper right. Vehicles and accompanying figures occupy designated positions relative to the main deity. Thrones, pedestals, and architectural frames maintain prescribed relationships to the central figure. These placement rules ensure iconographic correctness and maintain continuity with sculpture, manuscript illustration, and other Hindu artistic traditions.

Comparison with Other Indian Painting Styles

Tanjore Painting vs Mysore Painting

Tanjore and Mysore paintings share sufficient similarities—gold work, gesso relief, devotional subjects—that casual observers might confuse them. Both styles emerged in South India’s royal courts and serve similar devotional functions. However, careful examination reveals significant differences in technique, materials, and aesthetic priorities.

Mysore paintings typically employ gold leaf more sparingly, using it primarily for jewelry and select decorative elements rather than the lavish application characteristic of Tanjore work. The gesso relief in Mysore paintings tends to be more subtle, creating gentler three-dimensional effects. Color palettes differ as well, with Mysore paintings favoring softer, more pastel hues compared to Tanjore’s bold primaries. The overall impression of Mysore painting is one of delicate refinement, while Tanjore painting projects regal opulence.

Differences Between Tanjore and Mughal Painting

Mughal miniature painting developed under Islamic patronage in North India, creating an aesthetic dramatically different from Tanjore’s temple traditions. Mughal paintings employ naturalistic perspective, subtle gradations of color, and atmospheric effects that create convincing three-dimensional space. Figures receive modeling through careful shading, creating volumetric forms rather than flat iconic presences.

Subject matter diverges equally sharply. Mughal paintings depict courtly life, portraits, hunting scenes, and historical events alongside occasional religious themes drawn from Islamic tradition. The emphasis falls on worldly magnificence and documentary accuracy rather than spiritual transcendence. Technically, Mughal miniatures use watercolor on paper, allowing fine detail impossible on the textured gesso surfaces of Tanjore paintings. These fundamental differences in materials, techniques, and cultural contexts create completely distinct artistic languages despite occasional cross-influences.

Tanjore Painting vs Pahari and Rajput Styles

The Pahari and Rajput painting traditions of North India’s hill regions and desert kingdoms developed sophisticated miniature techniques that contrast with Tanjore’s approach. These styles, while depicting Hindu deities and mythological subjects similar to Tanjore paintings, employ Persian-influenced compositions, sophisticated color gradations, and lyrical sensibilities reflecting their regional aesthetic preferences.

Pahari paintings are particularly noted for their emotional subtlety and narrative sophistication, depicting Krishna’s divine romance with the gopis or Rama’s forest exile with poetic delicacy. Rajput paintings display bold colors and dynamic compositions but within the miniature format rather than the panel-painting scale of Tanjore works. Neither tradition employs the heavy gold embellishment or gesso relief that define Tanjore painting, preferring instead the refined techniques possible in manuscript-scale production.

Tanjore Painting and Mysore Painting: A Detailed Comparison

Differences in Gold Usage

The application of gold leaf provides the most immediately visible distinction between Tanjore and Mysore paintings. Tanjore artists apply gold across large areas—entire backgrounds, extensive garment sections, elaborate architectural frames—creating a dominant golden presence that often exceeds the painted areas in visual impact. The gold in Tanjore paintings functions as a primary compositional element rather than an accent.

Mysore paintings treat gold more conservatively, restricting it primarily to jewelry, crown details, and select decorative highlights. The painted areas dominate, with gold providing refinement rather than overwhelming presence. This difference reflects both economic factors—Mysore painters adapted to reduced patronage earlier than their Tanjore counterparts—and aesthetic preferences that favored subtlety over opulence.

Stylistic and Color Variations

Beyond gold usage, the color palettes of these traditions diverge significantly. Tanjore paintings employ saturated primary colors—brilliant reds, deep blues, vibrant greens—applied in flat, unmodulated areas. The intensity of these hues matches the gold’s brilliance, creating overall compositions of maximum visual impact. Mysore paintings prefer softer, more harmonious color schemes with subtle variations and gentler contrasts.

Stylistic differences extend to figural treatment as well. Tanjore deities display bold, iconic presences with strong outlines and geometric simplification. Mysore figures appear more delicate, with refined features and graceful proportions that suggest courtly elegance rather than divine majesty. The overall impression differs profoundly—Tanjore paintings project power and magnificence, while Mysore works emphasize beauty and refinement.

Regional Influences

The geographical and cultural contexts of Thanjavur and Mysore shaped their respective painting traditions distinctly. Thanjavur, located in the Kaveri delta’s fertile plains, enjoyed agricultural prosperity that supported lavish artistic production. The city’s temples housed some of South India’s greatest Chola bronzes and medieval murals, providing visual precedents that emphasized monumentality and divine grandeur.

Mysore, the capital of a smaller kingdom in Karnataka, developed its painting tradition under different pressures. The Wodeyar rulers maintained refined court culture that emphasized literary and artistic sophistication rather than sheer magnificence. This context encouraged painting styles that demonstrated technical finesse and aesthetic sensitivity, qualities that could be achieved without the massive resource expenditure required for Tanjore’s gold-heavy approach.

Role of Tanjore Painting in Indian Art History

Contribution to South Indian Visual Culture

Tanjore painting represents a crucial link in South India’s visual heritage, connecting temple mural traditions with portable devotional art. The style synthesized elements from multiple sources—Chola bronze iconography, temple architecture’s decorative vocabularies, textile design patterns—into a cohesive aesthetic that became distinctively South Indian. This synthesis demonstrates the region’s capacity to absorb and integrate influences while maintaining cultural identity.

The art form’s influence extended beyond painting itself. The iconographic conventions established in Tanjore works informed other media, including print-making, calendar art, and even contemporary visual design. The characteristic gold-and-color aesthetic became synonymous with South Indian religious art, shaping popular visual culture in ways that persist today. Tanjore painting thus functions not merely as a historical artifact but as a living influence on regional visual imagination.

Influence on Devotional Art Traditions

Tanjore painting established templates for devotional imagery that spread far beyond their place of origin. The format of deity portraits with rich ornamentation and gold embellishment became standard for home worship across South India and diaspora communities worldwide. Affordable lithograph prints and posters adapted Tanjore aesthetics, making the visual language accessible to people who couldn’t afford original paintings.

This democratization of Tanjore imagery transformed Hindu devotional practices. What began as royal and temple art became available for domestic worship, enabling families to create sacred spaces in their homes that mimicked temple environments. The paintings’ portability allowed people to carry their deities when relocating, maintaining devotional continuity across geographical distances. This accessibility fundamentally altered the relationship between visual art and popular religiosity in modern Hinduism.

Academic and Exam Relevance (UPSC, TGT/PGT Art)

Tanjore painting features prominently in academic curricula and competitive examinations focused on Indian culture and art history. Questions about the art form appear regularly in UPSC civil services examinations, state public service tests, and teaching certification exams. Knowledge of Tanjore painting—its origins, characteristics, techniques, and cultural significance—constitutes essential preparation for candidates pursuing careers in cultural administration, education, and heritage management.

The art form serves educational purposes beyond memorization of facts. Studying Tanjore painting provides insights into broader themes—the relationship between royal patronage and artistic production, the role of religious devotion in cultural preservation, the tension between tradition and innovation, and the challenges facing heritage crafts in modern economies. These themes resonate across disciplines, making Tanjore painting a valuable case study in courses ranging from art history to sociology to economics.

Famous Tanjore Paintings and Masterpieces

Classic Krishna Tanjore Paintings

Krishna, the divine cowherd and cosmic preserver, has inspired countless Tanjore masterpieces. The most celebrated include depictions of Venugopala Krishna—the flute-playing deity standing in tribhanga pose beneath a tree, his divine music captivating all creation. These paintings showcase Tanjore aesthetics at their finest, with elaborate gold-worked jewelry, richly decorated garments, and serene expressions that embody divine charm.

Balakrishna (infant Krishna) representations form another beloved category, showing the deity crawling while stealing butter or standing with one foot playfully raised. These paintings capture the paradox central to Krishna devotion—the supreme divine manifesting as a mischievous child, making the infinite accessible through intimacy. The finest examples balance opulent decoration with the innocence appropriate to childhood, creating images that inspire both reverence and affection.

13.2 Coronation and Darbar Scenes

Coronation paintings represent Tanjore art’s most complex compositional achievements. These works depict Rama’s coronation after returning from exile, showing the deity enthroned with Sita, surrounded by brothers, sages, and celestial beings. The throne itself becomes a showcase for artistic virtuosity, featuring elaborate gesso relief work covered in gold, with every architectural detail meticulously rendered.

Darbar scenes, showing deities receiving worship or holding court, allowed artists to demonstrate their ability to organize multiple figures hierarchically within unified compositions. Gods and goddesses occupy raised thrones while devotees, attendants, and subsidiary deities arrange themselves in registers according to status. These paintings functioned as visual theology, explaining divine hierarchies and proper devotional relationships through spatial organization and iconographic precision.

Rare Antique Panels

The most valuable Tanjore paintings are antique pieces from the Maratha period, particularly works created during the 18th and early 19th centuries. These paintings represent the tradition at its apex, when royal patronage ensured access to the finest materials and most skilled artists. Collectors and museums prize such works not merely for age but for technical excellence and historical significance as documentation of devotional culture and artistic achievement.

Certain rare themes command particular attention—unusual iconographic forms, narrative paintings depicting lesser-known episodes, or works combining Hindu and Jain imagery reflecting syncretic religious environments. Paintings with documented royal provenance or attribution to named master artists achieve premium valuations. The authentication of such works requires expertise in materials analysis, stylistic evaluation, and historical documentation, making the market for antique Tanjore paintings both specialized and occasionally contentious.

Traditional Artists and Artisan Communities

Hereditary Painters of Thanjavur

Tanjore painting traditionally belonged to specific communities who passed skills through family lines across generations. These hereditary artists, known as chitrakars, maintained workshops where multiple family members worked collaboratively on paintings. The patriarch often executed critical elements like facial features while trained sons and nephews handled preliminary work and decorative details. This family structure ensured quality control and knowledge preservation while distributing labor efficiently.

These artist families enjoyed social prestige within their communities despite economic vulnerabilities. Royal and temple patronage provided periodic commissions, while wealthy merchants and landowners commissioned works for home worship. The relationship between patron and artist often extended across generations, with families maintaining loyalties that ensured continued work. This social fabric sustained artistic practice even during periods of political instability or economic hardship.

Gurukul System of Training

Traditional training followed the gurukul system, where students lived with master artists, learning through observation, imitation, and gradual assumption of responsibilities. Young apprentices began by preparing materials—grinding pigments, mixing adhesives, preparing wooden panels—before graduating to simpler painting tasks. Years passed before students attempted complete works independently, and mastery of the art form required a decade or more of intensive training.

This educational approach transmitted not just technical skills but aesthetic sensibilities and devotional attitudes essential to creating sacred art. Students learned to view their work as spiritual service rather than mere craft, understanding that paintings would become objects of worship requiring appropriate reverence during creation. The guru-student relationship carried lifelong obligations, with successful artists maintaining ties to their teachers and supporting their teachers’ families, perpetuating networks of mutual support within the artistic community.

Anonymous Masters and Folk Traditions

While some master artists achieved recognition and patronage that preserved their names, many remained anonymous, their works unsigned and their biographies lost to history. This anonymity partly reflects traditional attitudes that emphasized divine inspiration over individual creativity—the artist served as a channel for sacred imagery rather than an autonomous creator. Additionally, the collaborative nature of production made individual attribution complex, as multiple hands contributed to each painting.

Folk traditions running parallel to court-sponsored production created simpler paintings using similar techniques but with reduced material expense and less refined execution. These works served village temples and common households, making devotional imagery accessible beyond elite circles. While art historians have historically privileged royal commissions, recent scholarship recognizes folk productions’ importance in sustaining artistic knowledge during patronage crises and maintaining broader cultural engagement with the tradition.

Decline and Challenges Faced by Tanjore Painting

Loss of Royal Patronage

The dissolution of indigenous kingdoms under British colonial consolidation eliminated the primary economic foundation supporting Tanjore painting. Royal courts that had commissioned hundreds of paintings annually disappeared, and with them went the steady income that sustained artist communities. The British administration showed limited interest in indigenous arts, preferring European aesthetic standards and regarding traditional Indian practices as curiosities rather than living traditions deserving support.

Temple patronage, the other major source of commissions, also declined as colonial policies diverted temple revenues to state control. Temples that had previously commissioned paintings for renovations, festivals, and gifting to devotees could no longer afford such expenses. The combined loss of royal and religious patronage left artist families without viable markets, forcing many to abandon traditional practices for alternative livelihoods, creating a knowledge crisis as skills ceased transmission to younger generations.

Commercial Imitations

As demand for authentic Tanjore paintings declined, commercial producers began creating inferior imitations using cheaper materials and simplified techniques. These works substituted brass foil or gold paint for genuine gold leaf, used synthetic pigments instead of natural minerals, and eliminated or simplified the time-consuming gesso relief work. While superficially resembling traditional paintings, these commercial products lacked the quality and durability of authentic works.

The proliferation of imitations created multiple problems for the tradition. Consumers unfamiliar with authentic Tanjore paintings couldn’t distinguish quality work from cheap imitations, leading to market confusion and price depression. Serious artists found their works undervalued when compared to much cheaper alternatives. Additionally, the abundance of poor-quality paintings bearing the “Tanjore” name diluted the brand, making it difficult for genuine practitioners to command prices reflecting their skill and material costs.

Material Cost and Skill Erosion

The rising cost of traditional materials presented another formidable challenge. Gold prices increased substantially through the 20th century, making 22-carat gold leaf prohibitively expensive for all but the wealthiest patrons. Natural pigments became difficult to source as traditional suppliers disappeared and knowledge of material preparation faded. Even suitable wood became scarce as forests diminished and processed timber replaced traditional woodworking.

Simultaneously, the erosion of artistic skills accelerated as fewer young people entered training and elderly masters passed away. The gurukul system collapsed under economic pressures—families couldn’t afford to support apprentices for years without income, and young people sought education promising better economic prospects. Critical knowledge about material preparation, gesso formulation, and complex iconography risked permanent loss, threatening the tradition’s continuity even if market demand recovered.

Revival and Government Support

Role of Government Handicraft Boards

Post-independence India recognized traditional arts as national heritage requiring preservation and promotion. Government handicraft boards established programs supporting Tanjore painters through direct patronage, exhibitions, and institutional purchases. These boards commissioned paintings for government buildings, gifting to foreign dignitaries, and museum collections, creating demand independent of private markets and religious institutions.

Training programs reconnected elderly master artists with new students, documenting techniques and providing structured learning opportunities. Government-sponsored workshops offered stipends to both teachers and students, addressing the economic barriers that had prevented knowledge transmission. Exhibition tours across India and internationally raised public awareness about Tanjore painting, educating potential buyers and generating appreciation for the art form’s cultural significance.

GI Tag and Legal Protection

In 2007, Tanjore painting received Geographical Indication (GI) certification, legally protecting the name and establishing quality standards for authentic works. This certification, similar to protections for Champagne or Parmigiano-Reggiano, restricts use of the “Tanjore painting” designation to works produced in specified regions using traditional materials and techniques. The GI tag helps combat misrepresentation and provides legal recourse against producers falsely marketing inferior works as authentic Tanjore paintings.

The certification process required documentation of traditional techniques, material specifications, and historical practices, creating valuable archival resources. Implementation faces challenges, including limited enforcement capacity and market segments where buyers prioritize price over authenticity. Nevertheless, the GI tag represents important recognition of Tanjore painting’s cultural significance and provides tools for protecting the tradition against commercial dilution.

Art Institutions and Workshops

Art schools and cultural institutions have integrated Tanjore painting into curricula, providing institutional support and contemporary relevance. Students pursuing degrees in traditional arts can specialize in Tanjore painting, receiving formal education that complements traditional apprenticeship models. These programs combine technical training with academic study of art history, iconography, and conservation, producing artists with both practical skills and theoretical knowledge.

Private workshops and cultural centers offer short-term courses for hobbyists and enthusiasts, creating new constituencies for the art form. These programs don’t necessarily aim to produce professional artists but foster appreciation and basic understanding of techniques, expanding the community of people invested in the tradition’s survival. Some workshops focus on specific aspects—gold work, gesso relief, iconographic drawing—allowing intensive study of particular skills.

Modern and Contemporary Tanjore Paintings

Fusion with Contemporary Themes

Contemporary artists are exploring Tanjore techniques with non-traditional subjects, creating fusion works that maintain aesthetic elements while expanding thematic possibilities. Secular subjects including historical figures, national symbols, and abstract compositions receive Tanjore treatment—gold embellishment, gesso relief, bold colors—creating connections between traditional techniques and modern concerns.

These experiments generate controversy within the artistic community. Purists argue that Tanjore painting’s identity is inseparable from its devotional function and that applying techniques to secular subjects violates the tradition’s essential character. Progressives counter that adaptation ensures relevance and survival, attracting new audiences and creating market opportunities unavailable within exclusively religious frameworks. This tension between preservation and innovation characterizes many heritage crafts negotiating modernity.

Tanjore Painting in Home Decor

The decorative appeal of Tanjore paintings has found appreciation beyond religious contexts. Interior designers incorporate these works into secular spaces, valuing them for aesthetic impact rather than devotional function. The gold surfaces and rich colors complement both traditional and contemporary design schemes, with paintings serving as focal points in living rooms, offices, and hospitality spaces.

This decorative market has both positive and negative implications. It creates demand supporting artist livelihoods and introduces the art form to audiences unfamiliar with its religious significance. However, it also risks reducing sacred art to mere decoration, stripping away spiritual meanings essential to the tradition. Some artists embrace this market while maintaining devotional work separately; others refuse commissions for purely decorative purposes, preserving the art form’s sacred character even at economic cost.

Digital and Miniature Adaptations

Technology has enabled new formats for Tanjore aesthetics. Digital artists create computer-generated images mimicking Tanjore painting characteristics—gold effects, relief simulations, iconic compositions—for applications ranging from greeting cards to website designs. These digital adaptations spread Tanjore visual language while raising questions about authenticity and the importance of traditional materials and handwork.

Miniature Tanjore paintings have emerged as affordable alternatives to full-scale works. These smaller pieces, sometimes just a few inches across, employ traditional techniques at reduced scale, making authentic works accessible to buyers unable to afford large paintings. The miniature format presents technical challenges, as gesso relief and gold application become more difficult at tiny scales, but skilled artists produce remarkable works that maintain quality standards despite size constraints.

How to Identify an Authentic Tanjore Painting

Quality of Gold Foil

Authentic Tanjore paintings employ 22-carat gold leaf rather than brass foil or gold paint. Genuine gold maintains a warm, consistent color that doesn’t tarnish or fade over time. Under close inspection, gold leaf shows a characteristic texture—slightly rippled from the laying process, with edges that overlap rather than meeting in perfect lines. Brass foil or paint appears flatter and more uniform, lacking the depth and luminosity of real gold.

Testing gold authenticity requires expertise and sometimes laboratory analysis, but visual inspection can reveal obvious imitations. Brass develops a greenish tinge over time, while gold paint shows brushstrokes and uneven coverage. The weight of a painting provides additional clues—genuine gold adds noticeable weight, while brass or paint contributes minimally. Suspicious uniformity or mechanical perfection suggests printed or stamped gold application rather than hand-laid leaf.

Embossed Relief Work

Authentic gesso relief work shows hand-crafted irregularities and organic transitions between raised and flat areas. The relief should integrate seamlessly with the painted surface, not appearing as added elements. High-quality gesso features fine detail work—individual pearls in necklaces, petals in floral motifs, architectural ornaments—that demonstrate artistic skill and patience.

Imitations often use molded or stamped relief that shows mechanical repetition and hard edges. Some commercial works eliminate relief entirely, using gold paint to simulate three-dimensionality. Viewing paintings from acute angles reveals true relief work through shadows and surface variations that painted simulations cannot replicate. The thickness and quality of gesso also matter—too thin and it chips easily; too thick and it cracks; properly applied gesso maintains flexibility and adhesion indefinitely.

Certification and Artist Signature

Provenance documentation and artist certification provide important authentication tools, though forgeries exist in this realm too. Reputable artists often provide certificates detailing materials used, creation date, and subject matter. Government craft boards and cultural organizations issue authentication certificates for works meeting traditional standards. These documents should include photographs of the specific work and official seals or signatures.

Artist signatures pose complications, as traditional works were often unsigned, making historical pieces impossible to attribute definitively. Contemporary artists increasingly sign their works, establishing personal brands and taking responsibility for quality. However, signatures alone don’t guarantee authenticity—famous artists’ signatures can be forged, and legitimate works by unknown artists carry no signatures. Authentication ultimately requires examining multiple factors—materials, techniques, style consistency, provenance—rather than relying on single indicators.

Tanjore Painting in the Art Market

Pricing Factors

Multiple variables determine Tanjore painting prices. Size matters fundamentally—larger works require more materials and time, commanding higher prices. Material quality profoundly affects value: genuine 22-carat gold versus brass foil, natural versus synthetic pigments, proper wood versus composite boards. Technical execution counts heavily—relief work quality, gold application skill, painting refinement, and iconographic accuracy all impact valuation.

Artist reputation introduces another pricing dimension. Established artists with documented training lineages and exhibition histories command premiums over unknown practitioners. Historical pieces from recognized periods fetch collector prices far exceeding contemporary works. Rarity influences value—unusual subjects, exceptional preservation, or documented royal provenance can multiply prices exponentially. Market location matters too, with urban galleries achieving higher prices than rural artisan cooperatives, regardless of quality equivalence.

Antique vs Contemporary Works

Antique Tanjore paintings—particularly Maratha-period pieces from the 18th and 19th centuries—constitute a specialized collector’s market with prices ranging into tens of thousands of dollars for museum-quality examples. These works appeal to serious collectors, museums, and cultural institutions seeking historically significant examples. Authentication challenges and condition issues complicate this market, as restoration work can compromise historical integrity and value.

Contemporary Tanjore paintings occupy a more accessible market, with prices ranging from hundreds to several thousand dollars depending on size, quality, and artist reputation. These works appeal to devotees seeking worship images, decorators wanting authentic traditional art, and cultural enthusiasts supporting living traditions. The contemporary market supports working artists directly, providing livelihoods that sustain the tradition, though prices often fail to reflect the true labor and material costs involved in quality production.

Collectors and Global Demand

Traditional South Indian families form the core collector base, acquiring Tanjore paintings for worship and cultural connection. Diaspora communities worldwide seek these works as links to heritage, creating international demand. Western collectors interested in Asian art have discovered Tanjore painting, appreciating its aesthetic qualities and technical sophistication. Museums increasingly acquire examples for permanent collections, recognizing the form’s art historical significance.

Online marketplaces have globalized access, connecting artists with buyers worldwide and removing geographical barriers. This development brings opportunities and risks—artists access broader markets but face competition from commercial producers and imitations. Collectors gain unprecedented access but must navigate authentication challenges without physical inspection. The digital marketplace’s evolution continues reshaping how Tanjore paintings are bought, sold, and valued in contemporary art economies.

Educational Importance of Tanjore Painting

Relevance for Art Students

Art students studying Indian cultural heritage must understand Tanjore painting as a major tradition showcasing distinctive technical approaches and cultural values. The art form demonstrates how religious devotion can drive aesthetic innovation, how royal patronage shapes artistic production, and how traditional crafts negotiate modernity. These lessons extend beyond art history to illuminate broader cultural dynamics.

Practical study of Tanjore techniques benefits students pursuing traditional arts careers or conservation work. Understanding gesso preparation, gold leaf application, and iconographic systems provides skills applicable to heritage conservation and authentic reproduction work. Even students specializing in contemporary art gain perspective on material experimentation and the relationship between technique and meaning through Tanjore painting study.

Importance in Indian Art Syllabi

School and university curricula across India include Tanjore painting as essential content in art, culture, and history courses. Students learn about the tradition’s development, characteristics, and cultural significance as part of understanding regional artistic diversity. The subject appears in state board examinations, making competent knowledge necessary for academic success in arts and humanities tracks.

Higher education programs in art history, museum studies, and cultural management devote substantial attention to Tanjore painting within South Indian art surveys. Research opportunities abound—technical studies of materials and methods, iconographic analysis, socio-economic studies of artist communities, market research, conservation challenges. Graduate students produce theses and dissertations advancing scholarly understanding while developing expertise supporting careers in cultural institutions.

MCQs and Competitive Exam Value

Competitive examinations testing cultural knowledge—civil services, teaching certification, cultural affairs positions—regularly include questions about Tanjore painting. Candidates must know basic facts: origin in Thanjavur, Tamil Nadu; characteristic gold leaf and gesso relief; religious subject matter; royal patronage; distinction from Mysore painting. More detailed questions may address specific techniques, historical periods, or cultural significance.

Preparation resources for competitive exams include sections on Tanjore painting within broader Indian art and culture chapters. Question formats range from factual recall to analytical comparison and critical evaluation. Success requires not merely memorizing facts but understanding relationships between artistic characteristics, historical contexts, and cultural meanings. Tanjore painting thus serves both as specific knowledge content and as exemplar for thinking critically about cultural heritage.

How to Learn Tanjore Painting

Beginner Materials Checklist

Aspiring Tanjore painters need specific materials to begin practice. The basic checklist includes: a prepared wooden board or commercially available pre-gessoed panel, cotton cloth, limestone powder and adhesive for gesso preparation, 22-carat gold leaf (or practice with imitation gold initially), natural or synthetic pigments in basic colors, brushes of various sizes, and tools for embossing gesso work. Additional supplies include tracing paper for design transfer, pencils, and reference images for iconographic accuracy.

Material quality dramatically affects learning outcomes. Beginners often start with synthetic materials and pre-prepared surfaces to reduce costs while developing skills. As proficiency increases, practitioners graduate to traditional materials and complete ground preparation. Many suppliers now cater specifically to Tanjore painting students, offering beginner kits that include essential materials with instructions. Investment in quality brushes proves particularly important, as inferior brushes make detailed work frustrating and compromise final results.

Offline Classes and Workshops

Traditional learning through direct apprenticeship remains available in Thanjavur and other centers where artist communities persist. These immersive experiences provide access to authentic techniques and cultural contexts that no other learning method can replicate. Students work alongside practicing artists, observing master-level execution while performing progressively complex tasks under supervision. Duration varies from intensive weeks-long workshops to multi-year apprenticeships.

Cultural centers, art schools, and government craft institutions across India offer structured Tanjore painting courses. These programs combine practical training with theoretical instruction about history, iconography, and cultural context. Class sizes range from small groups ensuring individual attention to larger workshops introducing basic techniques. Some institutions offer certification programs recognized for teaching credentials or craft business licensing. Regional variation exists in teaching approaches, with some emphasizing traditional methods exclusively while others incorporate contemporary adaptations.

Online Courses and Certifications

Digital platforms have democratized access to Tanjore painting instruction, allowing anyone with internet connectivity to learn regardless of geographical location. Video-based courses demonstrate techniques step-by-step, enabling students to pause, replay, and learn at individual paces. Some platforms offer live interactive sessions where instructors provide real-time feedback on student work. Online learning communities connect practitioners globally, facilitating knowledge exchange and mutual support.

Certification programs vary in rigor and recognition. Serious online courses require submission of completed works for evaluation, ensuring students achieve competency standards before certification. Others offer certificates merely for course completion without quality assessment. Prospective students should research instructor credentials, course curricula, and graduate outcomes before investing in online programs. While online learning cannot fully replace hands-on apprenticeship, it provides accessible entry points and supplementary instruction supporting skill development.

Cultural Symbolism and Aesthetic Philosophy

Spiritual Glow of Gold

Gold’s prominence in Tanjore painting transcends decorative function to embody profound spiritual symbolism. In Hindu philosophy, gold represents the eternal, incorruptible nature of divinity—it doesn’t tarnish, decay, or alter, mirroring the unchanging reality underlying phenomenal existence. The metal’s luminosity symbolizes divine light that dispels ignorance, with the painting’s golden glow manifesting the deity’s enlightening presence.

The economic value of gold adds another symbolic dimension, representing the devotee’s sacrifice and dedication. Using precious materials in sacred art demonstrates that nothing is too valuable to offer divinity. This principle extends from temple architecture adorned with gold to paintings where gold’s presence sanctifies the image. The act of viewing a gold-rich Tanjore painting thus involves not just aesthetic appreciation but recognition of both divine glory and human devotion materialized in precious metal.

Visual Grandeur and Divine Presence

Tanjore painting’s aesthetic philosophy prioritizes creating overwhelming visual impact that inspires awe and facilitates devotional experience. The combination of brilliant colors, radiant gold, and elaborate ornamentation creates sensory richness that draws viewers into contemplative engagement. This approach reflects Hindu temple aesthetics where abundance and complexity create sacred atmosphere, overwhelming mundane consciousness and preparing minds for spiritual experience.

The flat, iconic presentation serves specific devotional purposes. By eliminating naturalistic depth and maintaining frontal orientation, paintings create direct visual access between deity and devotee. The deity exists in sacred space separate from ordinary reality, yet the frontal pose acknowledges the viewer’s presence, enabling the reciprocal seeing that constitutes darshan. The lack of narrative elements or environmental detail focuses attention entirely on the divine figure, minimizing distraction and concentrating devotional energy.

Emotional Impact on Devotees

For believing Hindus, Tanjore paintings function as more than representations—they embody divine presence, becoming conduits for spiritual interaction. Daily worship before these images establishes intimate relationships between devotees and deities. The paintings witness family joys and sorrows, receive prayers during crises, and provide comfort through their constant, benevolent presence. Over time, paintings accumulate emotional significance, becoming irreplaceable family treasures independent of monetary value.

The aesthetic choices support this emotional connection. Gentle facial expressions invite trust and affection, while the figures’ beauty inspires love and devotion. The permanence of materials symbolizes eternal divine presence, offering stability in changing circumstances. Gold’s responsiveness to light creates dynamic visual experiences—paintings appear different in morning sunlight versus evening lamplight, suggesting the deity’s living presence. These emotional dimensions distinguish Tanjore paintings from secular art, explaining why authentic works continue finding devotional rather than merely decorative applications.

Preservation and Future of Tanjore Painting

Need for Artist Support

Sustaining Tanjore painting requires addressing the economic vulnerabilities of practicing artists. Many struggle to earn adequate livelihood despite possessing valuable skills and cultural knowledge. The time and material costs involved in authentic production exceed what most consumers will pay, creating persistent economic stress. Without viable income, artists cannot dedicate themselves fully to practice or invest in training next generations.

Support mechanisms must address multiple levels. Direct patronage through government commissions, institutional purchases, and private collectors provides immediate income. Fair pricing that reflects true costs educates consumers about authentic works’ value. Social recognition through awards, exhibitions, and media coverage validates artists’ contributions and attracts younger people to the field. Comprehensive support combining economic assistance, market development, and social prestige offers the best hope for sustaining artist communities.

Documentation and Archiving

Systematic documentation of Tanjore painting techniques, iconography, and history constitutes urgent preservation work. Elderly master artists possess knowledge that will disappear with their deaths unless captured through interviews, demonstrations, and detailed recordings. Photography and videography can document working methods, while written records preserve information about material sources, recipe formulations, and stylistic conventions.

Archival collections require proper conservation and accessibility. Museums and cultural institutions must maintain optimal storage conditions for paintings in their collections while making them available for research and public education. Digital archives enable global access to documentation, allowing researchers and students worldwide to study the tradition. However, digital resources cannot replace physical examination of original works, making conservation of actual paintings and maintenance of accessible collections equally crucial.

Role of Digital Platforms

Digital technology offers powerful tools for preservation and promotion. Virtual exhibitions make Tanjore paintings accessible to global audiences unable to visit physical collections. Educational websites and videos teach techniques and history, expanding the knowledge base beyond traditional artist communities. Social media platforms enable artists to showcase work, connect with patrons, and build markets beyond geographical limitations.

E-commerce platforms facilitate direct sales, eliminating intermediaries who traditionally captured substantial portions of sale prices. Online documentation projects preserve vanishing knowledge and make it accessible for future research and revival efforts. Digital tools also enable new forms of engagement—virtual reality experiences that simulate viewing paintings in temple or palace contexts, interactive educational programs that teach iconographic interpretation, and collaborative platforms connecting artists, scholars, and enthusiasts. While technology cannot replace traditional transmission methods entirely, it provides complementary preservation and dissemination strategies essential for contemporary cultural survival.

Tanjore Painting as a Living Tradition

Continuity Through Generations

Despite challenges, Tanjore painting persists as a living tradition with artists actively creating works using traditional methods. Hereditary artist families maintain practices transmitted through multiple generations, preserving technical knowledge and stylistic continuity. While numbers have declined from historical peaks, dedicated practitioners ensure the tradition doesn’t become merely a historical artifact but remains a living art form capable of producing new works of authentic quality.

This continuity depends on intergenerational transmission mechanisms. Older artists mentoring younger practitioners, whether family members or external students, keeps knowledge flowing forward. Some artist families have modernized transmission, incorporating contemporary educational approaches while preserving essential technical and cultural content. The combination of traditional apprenticeship values—patience, dedication, reverence for craft—with modern teaching methods creates hybrid systems suited to contemporary contexts while maintaining authentic practice.

Adaptability Without Losing Essence

Successful living traditions balance preservation with evolution, maintaining core identity while adapting to changed circumstances. Tanjore painting demonstrates this capacity through its history—absorbing Maratha influences while remaining recognizably South Indian, adjusting to reduced patronage without abandoning gold work, finding new markets without completely abandoning devotional functions. This adaptability explains its survival when rigidly traditional arts disappeared.